WAYS OF KNOWING DIARY

Vamos acompanhar semanalmente a jornada de Cris Takuá nas Living Schools e Veronica Pinheiro na Casa da Criança, na Escola Professor Escragnolle Dória no Rio de Janeiro. Saiba mais na página do Grupo Aprendizagens.

27/06/2024

TAKUAPU, ECO DO SOM DO SABER – por Cris Takuá

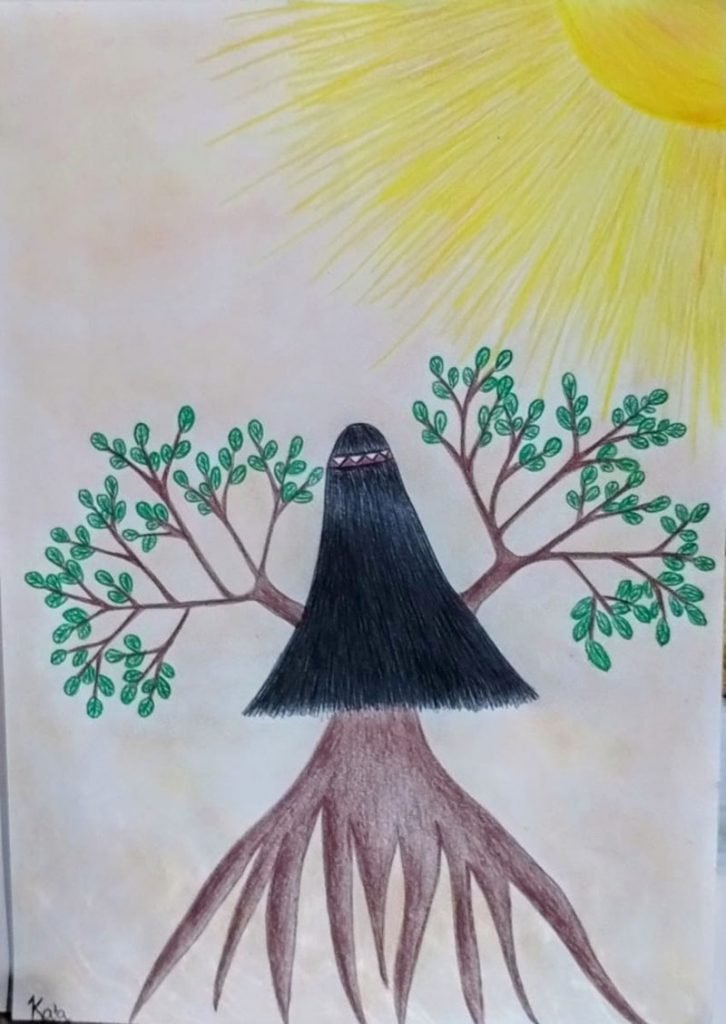

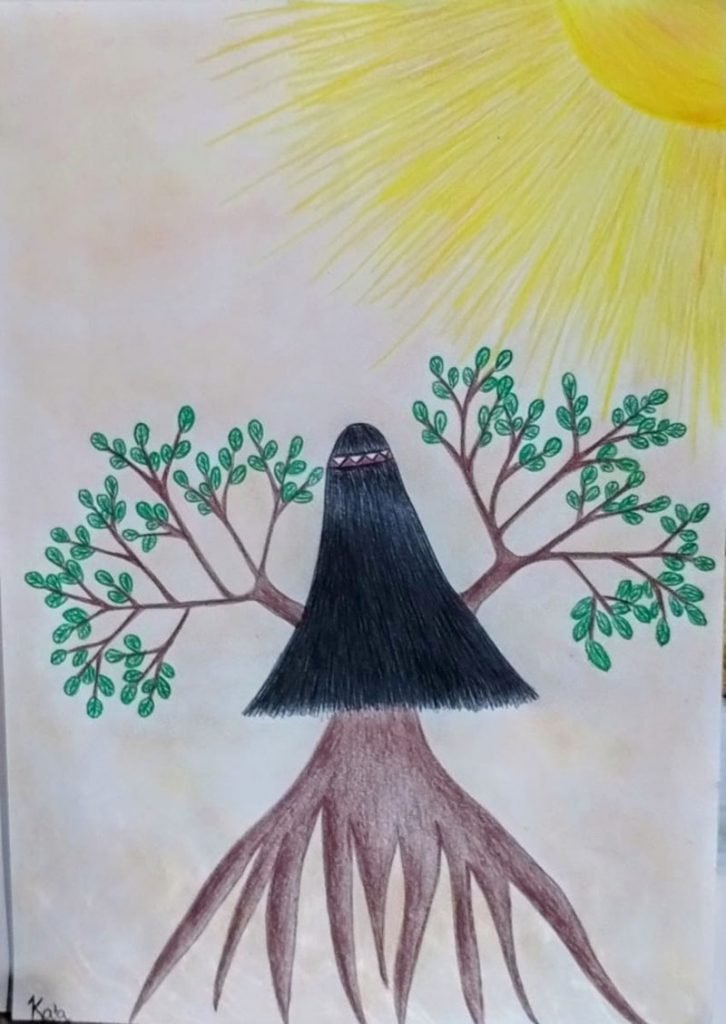

Arte: Cris Takuá

Arte: Cris Takuá

“Nhanderu ma ombojera raka’e takua’i, ramo haema kyringue kunhã’i oiko ramo ojapo huka’i tuu pe Takuapu’i há’e yn vy ma Ajaka’i, Nhanderu oikuaa huka’i raka’e kunhangue’i pe guãrã, nhandevy oeja nhande rete oapresenta haguã, há’evy há’epy nda’evei avakue pó rupi rive ju jaxevavai haguã, nhandere reko porã’ in haguã py nhanembou. Any ramo takua’i ipiru pa’i harami havi nhanderete nhaendu jaiko axy vy.”

“O Deus gerou a takuarinha, por isso, quando nasce a bebê menina, o pai faz um Takuapu’i (taquara sonora) ou Ajaka’i (cestinha). Nhanderu gerou takuarinha, para ser o símbolo das mulheres Guarani, por isso nós, mulheres, temos que ser bem cuidadas pelos homens. Não foi em vão que Nhanderu mandou nós pra Terra. Nosso corpo é sagrado, se não for bem cuidado, a takuarinha seca. É desse modo, que nos sentimos quando ficamos feridas por fora e na alma.”

Mariza de Oliveira, aldeia Itanhaém, Biguaçu/SC

Na concentração da noite enluarada se manifestam os cantos das mulheres que, em suas rezas, se conectam com os espíritos guardiões de tudo o que habita a floresta. No compasso desse entoar de vozes e pensamentos, ecoa no chão de terra batida o Takuapu, instrumento musical feito de takuara, que faz conexões entre o Céu e a Terra e entre o visível e o invisível. Em minhas sensíveis meditações alcancei o entendimento sobre o Eco do Som do Saber. Esse significado tão profundo desse instrumento me remete à força e à coragem de seguir em busca do equilíbrio, da serenidade e saúde do corpo, da mente e do espírito.

A Takuá tem muita utilidade na vida Guarani, além de ser um ser sagrado e de muita sabedoria. Com ela, as mulheres trançam a palha para fazer balaio, e também para fazer o telhado das casas. Também se faz o pari, para pegar peixe. São muito importantes todos os usos e a convivência com a takuara na vida Guarani. O Takuapu, esse bastão musical que as mulheres tocam durante sua reza, tarova e também mborai, é feito do tronco da takuara. As mulheres também têm conhecimento do uso da geleia da takuara para amaciar o cabelo e a pele. Das takuaras também nasce o takuaraxó, uma larva que brota no centro do tronco e serve como alimento. E do Takuaruçu, uma takuara específica, toda cheia de espinhos, nasce um takuaraxó que serve como medicina para orientar e dar visões tanto para o povo Guarani como para os Maxakali. As larvas da takuara só nascem a cada 30 anos e servem como um modo de contar a idade da pessoa. Se tem 30 anos, diz que tem uma takuara, se tem 60, duas takuaras. Tem gente que chega a viver três ou até quatro takuaras.

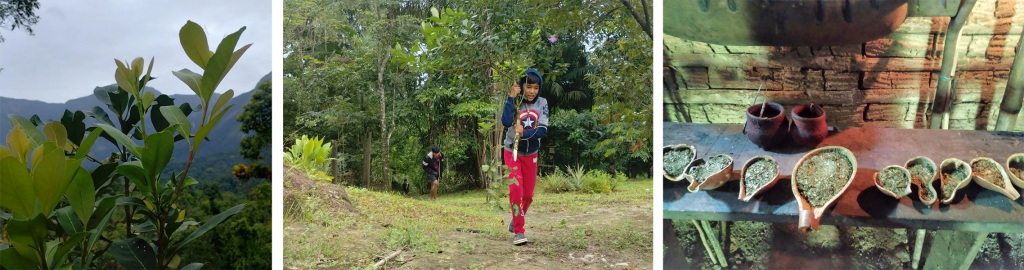

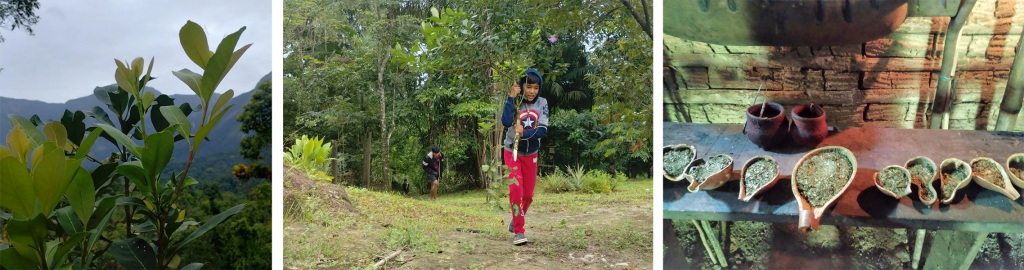

Foto: Carlos Papá

Foto: Carlos Papá

O ciclo de vida da takuara está relacionado ao conhecimento da vida Guarani. Com 30 anos, a takuara morre, seca, depois floresce e dá essa larva. A takuara tem um sumo quando amadurece, e as larvas vão comendo esse sumo. Então a takuara seca e as sementes caem, voam por aí. Os ratinhos, os passarinhos comem as sementes, mas algumas brotam. E o broto vai se espalhando, criando touceira.

Estamos observando que está diminuindo muito as takuara na floresta, possivelmente pelo aquecimento do clima da Terra, mas também porque os mais jovens não estão mais sabendo respeitar o ciclo de vida dela ou não estão mais se importando com isso e dessa forma. Ela não está conseguindo amadurecer e se espalhar como antes. Tudo na vida tem seu ciclo e seu tempo de se transformar e renascer. Respeitar o tempo de cada coisa é saber caminhar lentamente sobre o território.

Foto: Carlos Papá

Foto: Carlos Papá

Carlos Papá conta: “desde que a takuara surgiu no mundo, já fizeram coisas que não se devia fazer com ela, por isso ela se transformou em palha. A takuara, que a gente chama Takuá, é uma das filhas de Nhanderu Papá, nosso pai celestial. Dizem que Anhã, irmão de Nhanderu, queria ter uma companheira e se interessou por uma das filhas de Nhanderu, a linda Takuá. Anhã pediu ao seu irmão que a sobrinha pudesse o acompanhar pelo mundo. Nhanderu aprovou, mas disse que ela jamais poderia entrar na água. Poderia até se molhar, mas nunca mergulhar. Anhã ficou muito feliz, e Takuá o acompanhava em todos os lugares. Teve um dia em que eles foram até uma cachoeira. Anhã mergulhou na água e ela ficou olhando. Então ele a convidou para entrar, mas ela não quis por causa da recomendação do pai. Porém, Anhã não acreditou que haveria problema e a puxou pelo braço. Ele disse que o irmão implicava com tudo que era gostoso, por isso havia proibido. Takuá pediu então que Anhã não a soltasse. Ela estava gostando muito! Mas ele acabou soltando seu braço para que ela experimentasse mergulhar no rio. Não vendo mais a moça, Anhã tentou puxá-la novamente pelo braço e tirou da água um cesto. Ele começou a gritar por ela, mas só havia o cesto, que começou a se desfazer. Depois Anhã foi até o irmão com o cesto desfeito na mão. Disse que Takuá tinha desaparecido e ficou apenas aquela palha. Nhanderu pediu a palha e trançou de novo o balaio. Fez balainho bem bonitinho de novo e encostou de lado. Disse então a Anhã que agora Takuá não iria mais com ele, pois ela não lhe servia de companheira. Anhã disse que não queria mais aquela mulher porque ela era de palha e era muito complicada. Então Nhanderu disse à Takuá que ela ensinaria as mulheres como ser bela e fazer coisas bonitas. Takuá até hoje vive num lugar de Nhanderu amba, a morada celestial. Chamam Takuá as mulheres que têm o Nhe’e, o espírito, desse lugar. Elas são muito cuidadosas e verdadeiras, Takuakypy’y, as irmãs mais novas de Takuá.”

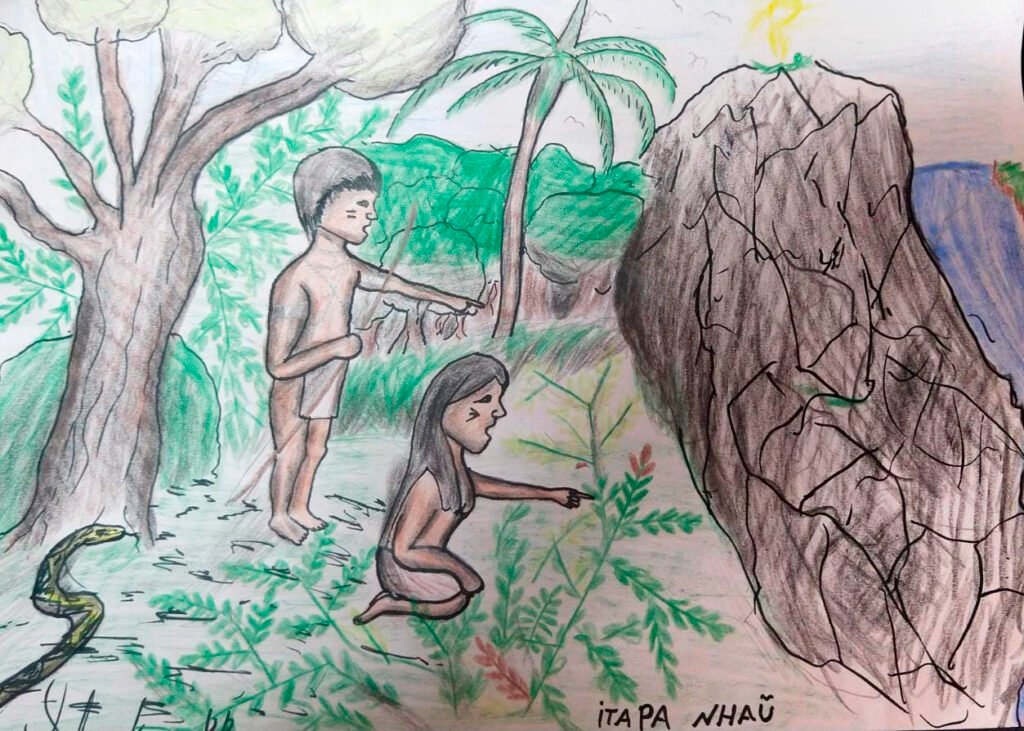

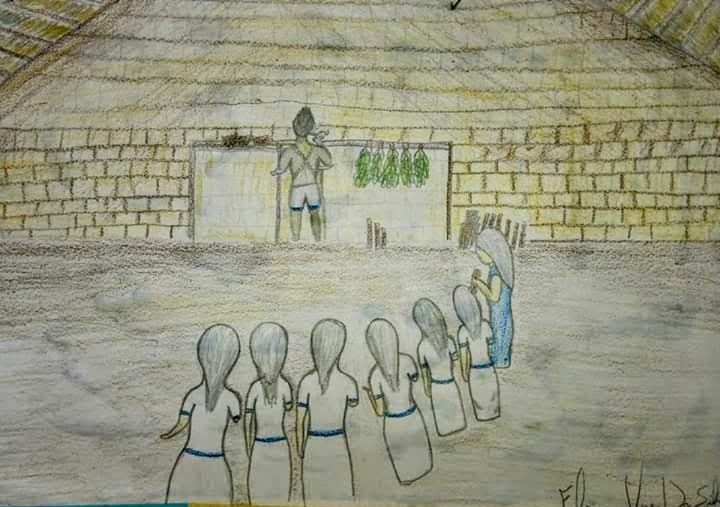

Arte: Wera Mirim

Arte: Wera Mirim

25/06/2024

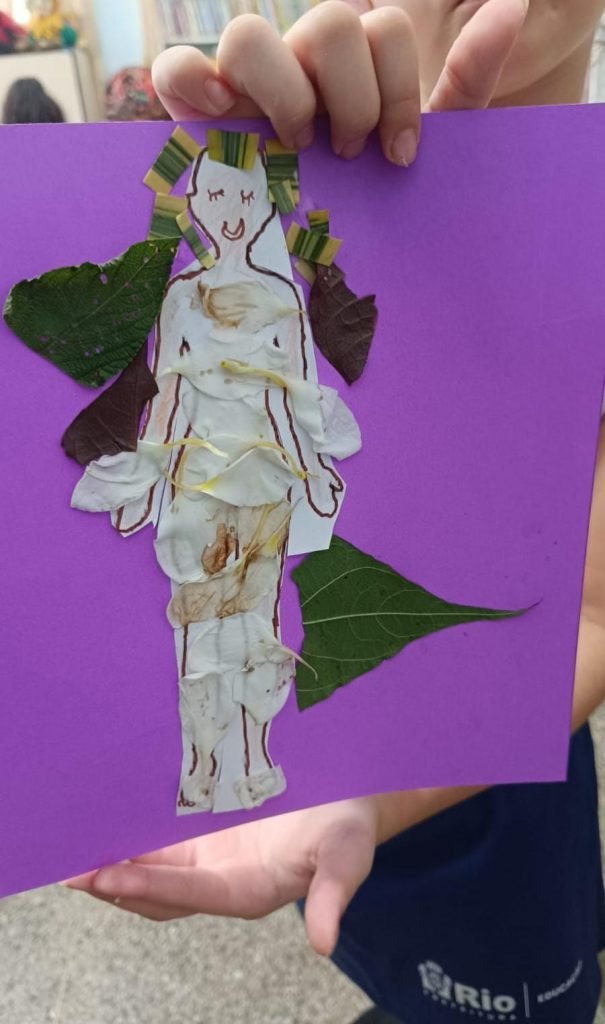

NA NATUREZA, NADA VIVE SOZINHO – por Veronica Pinheiro

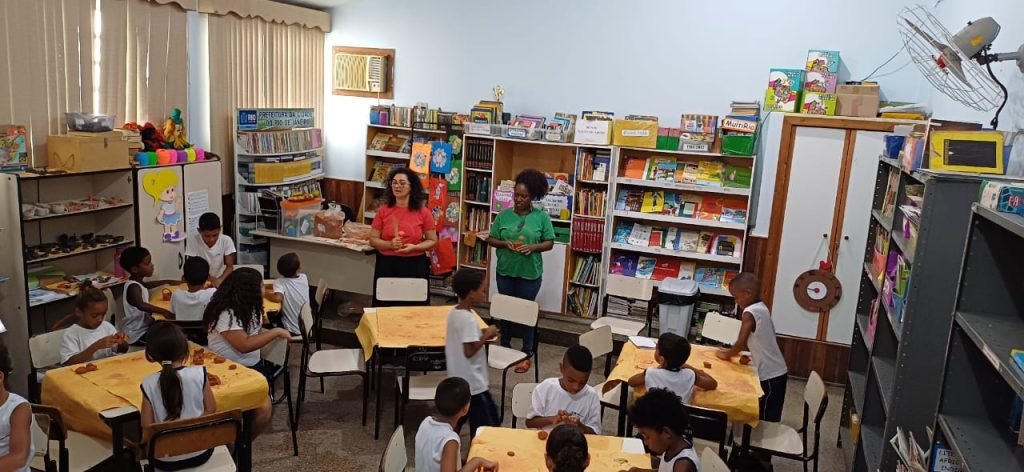

Foto: Wagner Clayton

Foto: Wagner Clayton

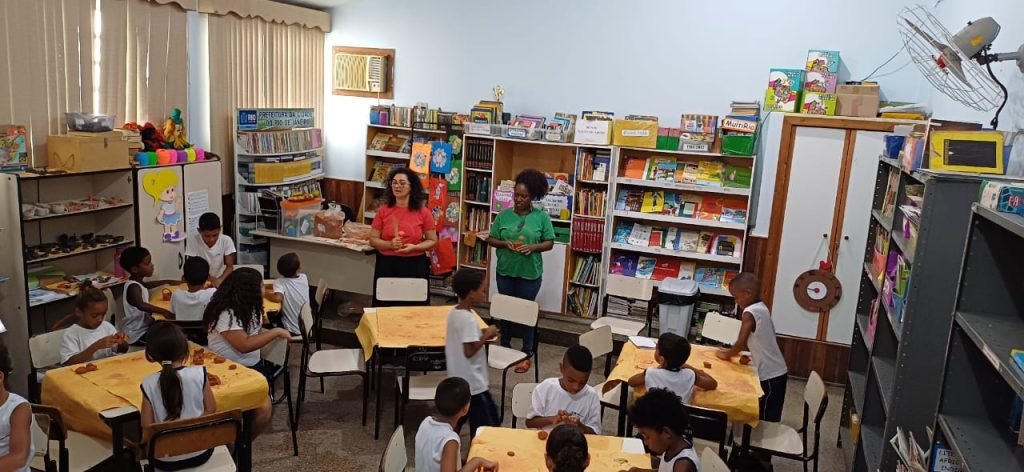

Começamos o último texto do semestre com as palavras da professora Miriam. Ela trabalha na Escola Escragnolle Dória em dois turnos, manhã e tarde, atendendo 62 crianças de 5 e seis anos de idade de segunda a sexta.

“Desde a chegada da equipe Selvagens em nossa escola, temos observado e experimentado um novo movimento dentro da escola. Tanto pelo acesso a materiais que não são tão comuns nas salas de aulas de escolas públicas, mas também por ter quem nos conduza a ter um olhar mais minucioso no que temos de mais rico ao nosso redor. Escolas em áreas conflagradas como as nossas, onde as crianças têm os ouvidos treinados para o tiro, fazê-las silenciar para ouvir os pássaros, o barulho do vento ou o que se passa dentro de si e transformar em arte, é quase mágico. Quase, a linha entre o mágico e o real é tão tênue que ora ou outra invadimos a sala de aula da colega para fotografar como uma urgência de querermos parar no tempo.

Vê-los pintar com a tinta que produziram a partir da terra encontrada no chão da escola, revelar fotos das folhas e galhos que caíram do quintal dali, observar a natureza que compõe o nosso território… Observar, criar, produzir. Uma sequência rica de significados que eu, enquanto professora, me dou o luxo e me permito também ser aluna naquele momento. Sento como meus alunos, espero meu pedaço de argila, me junto a eles com inúmeras perguntas, todos tentamos, fazemos o nosso melhor, sorrimos com o resultado, terminamos orgulhosos de nós mesmos pelo o que fomos capazes de criar. Voltamos para sala de aula certos de que todos somos talentosos, desmistificamos que todo professor sabe tudo. Voltamos para aula com um novo olhar sobre nós mesmos. Acho que todos que têm feito parte do projeto têm se sentido dessa forma. Somos levados a ter novas conclusões sobre nós mesmos, temos nos vistos como parte importante da natureza e temos percebido como ela nos impacta tanto quanto nossas ações a impactam.”

Anna Dantes, Madeleine Deschamps e eu tivemos longas conversas em dezembro de 2023 e janeiro de 2024 sobre caminhos de aprendizagens e sobre possibilidades de desdobramentos das oficinas e dos projetos realizados em 2023 com o Grupo Crianças. Falamos sobre criar vínculos com escolas e professores. Quando subitamente precisei retornar ao trabalho na Prefeitura do Rio, conversamos sobre como poderíamos ativar os estudos e pensamentos presentes nos ciclos Selvagem numa sala de aula. Em algum momento pensei em retornar ao trabalho como coordenadora pedagógica, mas aceitei o desafio de voltar como professora de sala de leitura numa escola de crianças. As crianças sempre estiveram presentes na minha vida, mas nunca estive como professora atendendo regularmente os pequenos em sala de aula.

Lembro de ficar feliz em me tornar a “professora da sala de leitura”. Lembro de rir e lembrar de minha avó lendo a borra do café na xícara, as nuvens e os olhos das crianças. Dorvelina, mãe de minha mãe, não sabia ler ou escrever em português, mas lia a vida e interpretava sonhos. Ler e interpretar, lá em casa, era coisa do cotidiano, quase nunca relacionada aos livros. “A gente olhava e lia a terra.” Tudo era texto e tudo poderia virar texto. Os livros chegaram lá em casa recentemente. Achei engraçado isso de ser a mediadora das rodas de leituras de uma escola de crianças. Agradeci em silêncio a gentileza que a vida me fez: estávamos diante da possibilidade de iniciar um percurso de Aprendizagens em diálogo com a vida.

O que é compartilhado nos diários é apenas uma parte do trabalho, pois nosso percurso é trilhado por muitos pés. Oficinas, passeios, organização de propostas e materiais só acontecem porque o Grupo Aprendizagens é formado por uma rede invisível que se expande, interligando cuidados preciosos. Chegamos ao Complexo da Pedreira sonhando despertar memórias e fortalecer as conexões das crianças com o território. Para além das problemáticas que tornam os dias difíceis, fazemos menção ao território ancestral, natural e orgânico. Lembramos às crianças e aos professores que somos natureza, natureza viva e pulsante.

Madá se preocupou com a carga horária semanal que eu teria de cumprir e como isso poderia me sobrecarregar. Juntas acreditamos e sonhamos orçamentos, passeios, oficinas e uma “festa cósmica” para o final do ano com crianças vestidas de estrelas e planetas. Encerramos o semestre felizes. Praticamos o bem viver numa terra que só é conhecida por seus males. O poeta disse que “Fundamental é mesmo o amor/É impossível ser feliz sozinho”. Apesar de todo desafio, tudo foi mais feliz e potente do que imaginávamos. A escola nos respondeu muito mais rápido do que esperávamos. Está sendo fundamental seguir em amor e juntos. Ubuntu, sou porque somos. Tal qual as árvores da floresta que só existem porque estão intimamente ligadas, o percurso Aprendizagens está intimamente ligado a uma teia de seres regenerantes.

Juntos aos relatos que recebemos de professores e grupos de pesquisas, neste semestre, fomos convidados pela Gerência de Relações Étnico-Raciais, da Secretaria Municipal de Educação da Prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro, para a IV Jornada da GERER – Caminhos e perspectivas para futuros possíveis¹. Como resposta ao convite, preparamos um Guia de Aprendizagens Selvagem, GAS, para ser compartilhado com 1544 Escolas Públicas de Ensino Fundamental na cidade do Rio de Janeiro. “Cuidado não é troca, é compartilhamento”, já dizia Nego Bispo. Não criamos nada. Quando chegamos ao Complexo da Pedreira, já existiam muitos outros compartilhantes que nos receberam. Desde o algodoeiro na entrada da escola aos pássaros que nos visitam todas as tardes, agradecemos a toda vida e a todos os seres que estiveram conosco neste semestre.

Àwúré

¹Material Complementar da Jornada de Relações Étinico-raciais. https://sites.google.com/view/gerer-sme/jornadas-da-gerer/iv-jornada-da-gerer

20/06/2024

A FORÇA DAS MONTANHAS – por Cris Takuá

Foto: Carlos Papá

Foto: Carlos Papá

Avózinha montanha

A força das pedras

Em meio à imersão da Espagiria

Muito profundos os ensinamentos

trazidos de tempos muito antigos

A cura é um delicado diálogo

Com os elementos

Com todos seres

Que nos possibilita a transformação

E tece laços de animação

Para o fortalecimento das crianças

dos Territórios

E o acordamento das memórias

Viva viva as Escolas Vivas

Viva os laboratórios vivos

Das Casas de Essências.

Foto: Ju Nabuco

Foto: Ju Nabuco

Caminhando por entre montanhas e vales, chegamos em São Gonçalo do Rio das Pedras em Minas Gerais, terra sagrada de muitas pedras e histórias. Lá, nesse lugar encantado, encontramos uma escola de verdade, uma Escola de Espagiria, coordenada por dois professores muito sensíveis e atentos aos mistérios profundos da natureza.

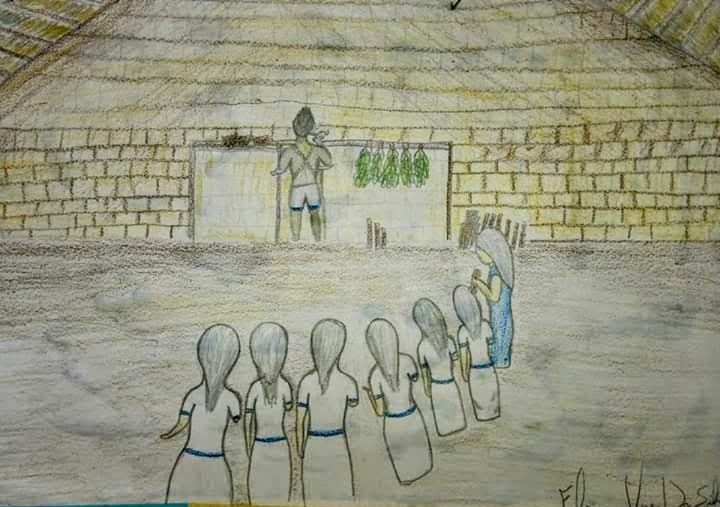

Durante três dias acompanhei os coordenadores das Escolas Vivas Guarani e Tukano-Desana-Tuyuka, e três jovens que foram junto. Falamos de História, Filosofia, Alquimia e Espagiria (a arte de produzir remédios, separar e unir, extrair e purificar através da sensível arte de conhecer a matéria dos seres).

Dialogamos sobre conhecimentos profundos e, através da troca entre o grupo reunido, sentimos que o conhecimento, quando entra dentro da gente, ele fixa e não sai mais. A partir das disposição em escutar com atenção nos permitimos sentir e perceber o que nos rodeia. Tudo o que desce do céu e sobe da Terra transmuta e nos orienta nessa caminhada de estudos e aprofundamentos na busca do Bem Viver.

Fotos: Ju Nabuco

Fotos: Ju Nabuco

O sonho das Escolas Vivas é ativar, animar e criar teias de afetos e cuidados, onde possamos caminhar cuidando de quem cuida e incentivar a semeadura dos saberes. Quando plantamos um jardim dentro nós a gente assume a responsabilidade de ser um agente multiplicador e capaz de ultrapassar a barreira do visível e a enxergar e dialogar com os seres invisíveis.

Um grande amante das plantas foi Paracelso, filósofo e médico do século XVI. Ele dizia que os humanos começam a adoecer quando se afastam de Deus, a natureza. Ele dizia que:

“Quem nada conhece, nada ama.

Quem nada pode fazer, nada compreende. Quem nada compreende, nada vale. Mas quem compreende também ama, observa, vê…

Quanto mais conhecimento houver inerente numa coisa,

Tanto maior o amor…

Aquele que imagina que todos os frutos amadurecem ao mesmo tempo, como as cerejas, nada sabe a respeito das uvas.”

Assim passamos três dias dialogando, colhendo plantas e preparando remedinhos e, nesses momentos tão sensíveis, aprendemos que a força do céu que está na planta desperta a força que habita em nós. Mas nos processos criativos de transformação da matéria precisamos de atenção e concentração. Pois a dispersão pela fala demasiada e a desatenção provocam o desperdício do tempo.

Foto: Ju Nabuco

Foto: Ju Nabuco

Dessa forma pude sentir e compreender a profunda relação com os elementos fogo, terra, água e ar e com os seres elementais: vegetais, animais, minerais e universais. Numa profunda conexão de tempos ancestrais onde filosofias Guarani, Tukano, Maxakali e lá do Egito se cruzaram e dialogaram numa profundeza encantadora.

Os jovens se inspiraram, cantaram, choraram e poetizaram suas percepções e inspirações de seguir caminhando, fortalecendo as Escolas Vivas e o sonho de alcançar a boa e bela forma de ser e estar em seus territórios.

Foto: Ju Nabuco

Foto: Ju Nabuco

______________

Esse encontro foi possível através da articulação de Ju Nabuco com Mestre Índio e Ana, professores da Escola de Espagiria, e das Escolas Vivas junto ao Selvagem, ciclo de estudos sobre a vida.

18/06/2024

ONDE ESTÁ A MATA? ESTÁ DENTRO DO PEITO – por Veronica Pinheiro

A sala de leitura da escola se assemelha a uma biblioteca em organização e funcionalidade. Livros em prateleiras, divididos por assunto; mesas grandes e cadeiras. Um espaço planejado e que leva em conta a área de armazenamento, a área de atividade, a área de circulação. Algumas regrinhas gerais são comuns em ambientes de leitura: entrar somente com o material necessário para o estudo; entrar de forma “disciplinada”; manter a voz e os gestos em tom discreto para não atrapalhar os demais leitores.

As primeiras histórias que conheci não estavam em livros guardados em prateleiras. As primeiras narrativas e lições que aprendi saiam da boca de Dona Cassiana, uma anciã, que ficava no final da tarde sentada num banco de madeira, sob o pé de aroeira, lá no morro onde nasci. Para saber o final de uma história, às vezes, tínhamos que esperar o dia seguinte ou ir atrás de Dona Cassiana enquanto ela cuidava das plantas. Ela rezava as crianças e dava colo enquanto rezava. Era uma reza-história, cantada e coreografada com folhas. Lembro de um dia ter procurado por ela e não a ter encontrado. Nunca mais a vi. Pouco depois do sumiço de Dona Cassiana, sumiu o banco e o pé de aroeira. Mas as palavras contadas, cantadas e rezadas me acompanham até hoje.

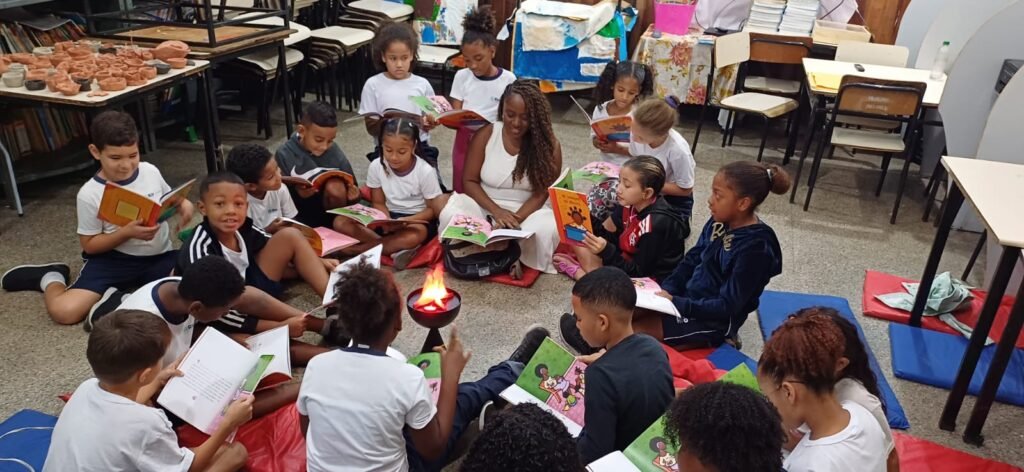

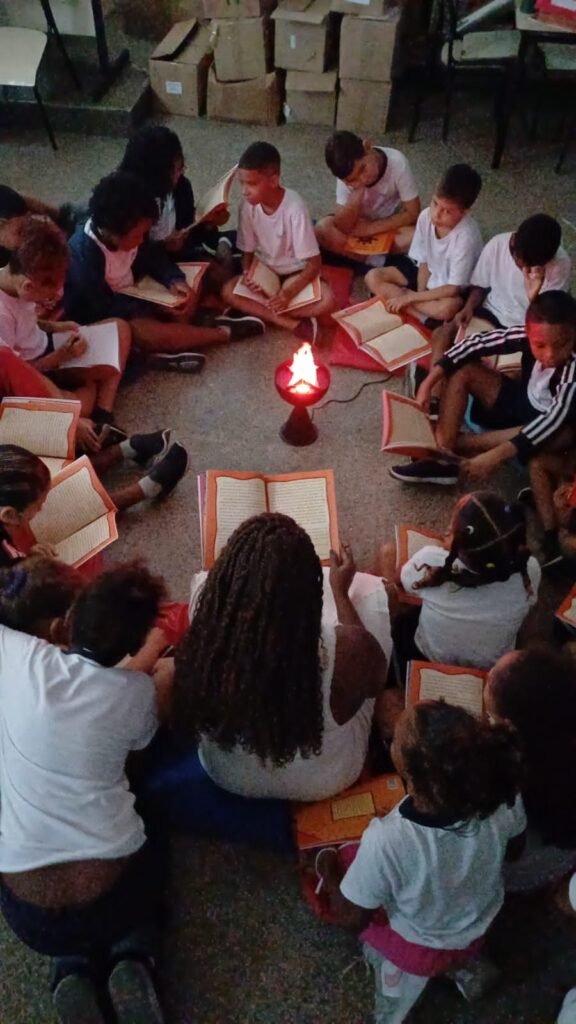

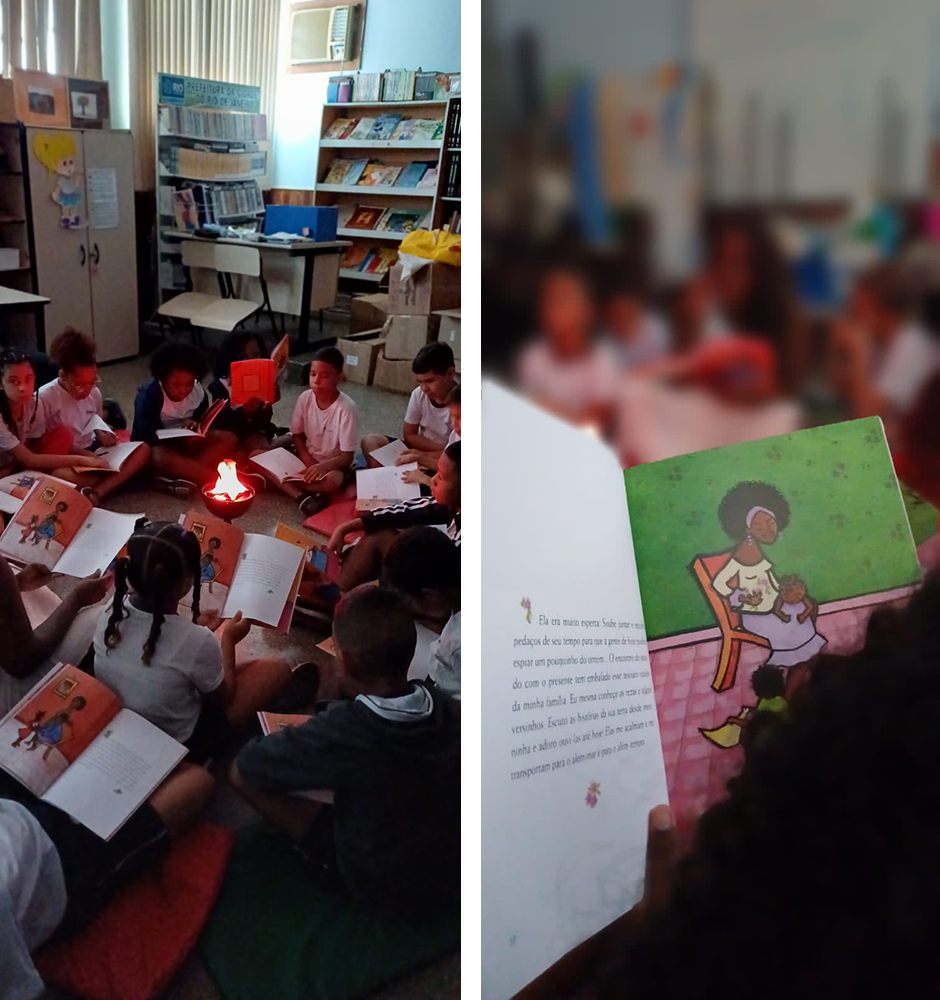

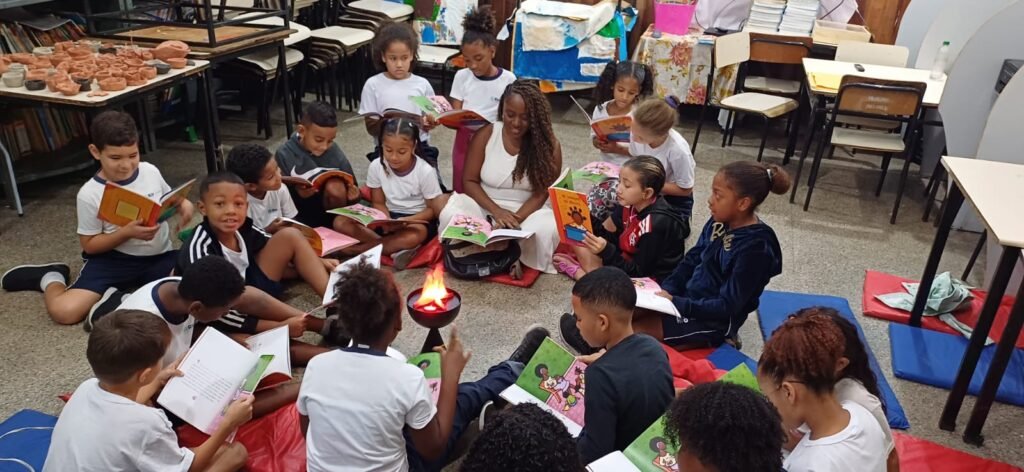

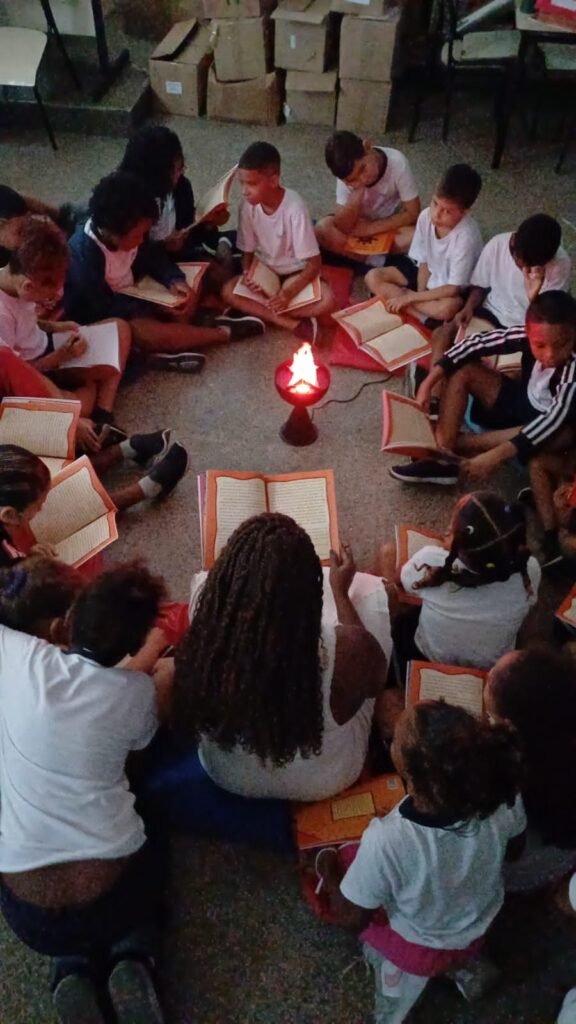

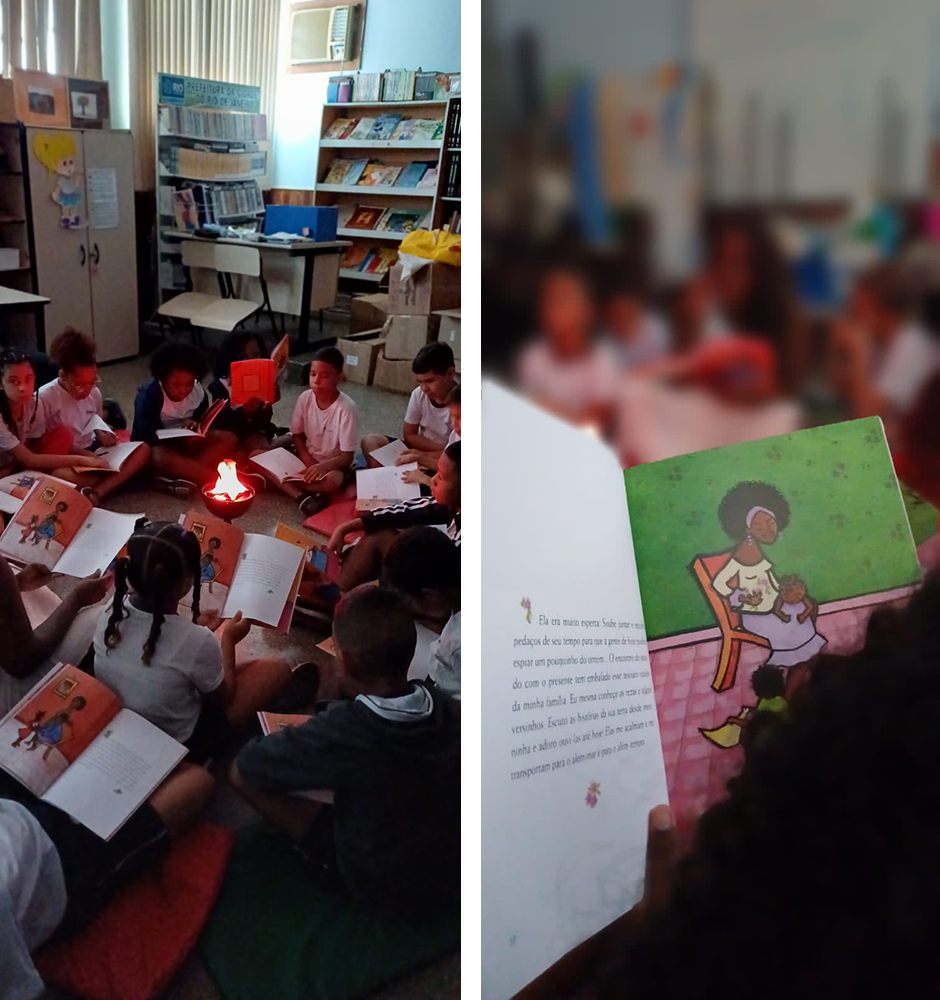

Hoje, sou a velha que conta quadras para meninos. Essa semana, cheguei à sala de leitura e retirei todas as cadeiras. Retirei também as mesas e apaguei as luzes. E acendi minha fogueira no meio da sala. No chão, colchonetes, 15 exemplares de um mesmo livro e eu sentada tal como a velha Cassiana ficava esperando por mim.

Aprendi com Carlos Papá que o escuro acolhe todos, não fazendo distinção de pessoas. E foi no escuro da sala que nos encontramos com as narrativas de avós e compartilhamos cuidados e gentilezas. “O que é isso?” “Um acampamento, você não está vendo” Eu acompanhei a entrada deles somente com olhos e ouvidos, nada falei. “É um acampamento sim. Olha a fogueira.” “Vamos sentar porque está de noite e frio.” Era 8h da manhã e fazia 31ºC do lado de fora da sala, dentro da sala tempo e lugar deslocavam-se sem convenções.

Eles sentaram em roda. A primeira turma que recebi neste dia tinha 28 crianças presentes, a maioria com 8 anos de idade, e estavam curiosas para saber o que iria acontecer. Na primeira ação, eles formariam duplas de leitores. Pedi para que um aluno que já soubesse ler se unisse a um colega que ainda não soubesse ler. Feitas as duplas, eles precisariam escolher um cantinho na sala de leitura para ler a história. Cada dupla se aninhou e se escondeu da forma que pode e desejou. Montaram cabaninhas e criaram tocas para ler. Disse a eles que a aprendizagem é um processo em que todos colaboram da forma que podem. Eles assumiram o cuidado com seus amigos de turma. Fiquei observando como lentamente quem ouvia ia escorregando pelo colchonete até deitar para ouvir atentamente as palavras lidas pelo amigo. E sem ter intencionado, naquele momento estabelecemos uma outra relação com aquele chão. Todas as vezes em que deitamos no chão da sala de leitura tinha sido para nos proteger do tiroteio. Pela primeira vez, não era o medo que nos levava ao chão. Era a terra nos ensinado a fortalecer vínculos. A professora da turma entra pensando que a sala estava vazia e se surpreende com a cena e os gestos. Sensivelmente, ela se retira sem ser percebida.

Nossa segunda ação era sentar ao redor da fogueira novamente. Agora a história seria lida por mim, e acompanhada por todos, cada um com um exemplar do livro nas mãos. Era uma solenidade, as chamas da fogueira de led aqueciam nossa roda. Comecei assim:

“Sônia Rosa, a autora do livro, dedica este livro aos seus dois sobrinhos-netos: Phelipe de Oliveira Nunes e Vitória Oliveira Silva. Eu, Veronica, dedico esta leitura aos meus alunos presentes sentados ao redor da fogueira comigo.”

Os tesouros de Monifa é a história de uma menina que, no dia de seu aniversário, foi escolhida para ficar com o “tesouro” de sua família. Monifa era o nome da bisavó da avó da menina. Monifa chega ao Brasil num navio negreiro e escreve muitos diários cheios de sonhos, rezas e canções. Minha voz tentou acompanhar a solenidade do momento, mas meus olhos decidiram por si só regar a terra. Não só os meus, mas muitos olhos regaram a terra naquele dia. À medida que líamos, mais perto ficávamos um dos outros. A roda logo se tornou um ninho. Uma mão pequena e macia colhia as lágrimas que me saiam dos olhos para não molhar o livro. Outras mãos me amparam os ombros e as costas. Mais um par de mãos percorriam minhas tranças.

Não me lembro de já ter chorado na frente de uma turma. No começo do ano eu era “a tia que dava colo” para as crianças que choravam na semana de adaptação. No meio do acampamento de leitura, eu era cuidada pelas crianças que entenderam que, no processo de aprendizagens, cada um coopera como pode. Passei então a receber cuidados. Eu li a história, e eles liam os bilhetes de Monifa.

Ao redor da fogueira, sentados no chão nos abraçamos no fim da leitura.

Alguém falou que no nosso acampamento só faltou uma coisa: “marshmallow”. Outro acrescentou que faltaram duas coisas: “marshmallow” e a mata. Antes que eu conseguisse formular resposta, Enzo, que parece nunca estar ouvindo o que falamos, disse: “Faltou só ‘marshmallow’ mesmo, a mata tá dentro da cabeça.”

Monifa significa “eu tenho sorte”. Cheia de mata dentro, ali eu era a pessoa mais sortuda do mundo.

Fotos: Wagner Clayton

13/06/2024

PALAVRAS SOPRADAS – por Cris Takuá

Arte de Juliana Russo

Arte de Juliana Russo

Boas e belas palavras

Massageiam a alma atenta.

Pensamentos invadem de magia meu ser

Em busca de entendimento

Dos mistérios das ciências da floresta.

As palavras como um sopro

Saem ecoando nossos pensamentos,

Voam e bailam no ar

Em busca dos conhecimentos,

Mas nem sempre se fazem

Claras e entendíveis

Aos seres que as recebem,

Podendo causar arrepio ou

Profunda emoção.

Como é difícil a suave comunicação

Em um mundo mergulhado em informação!

As palavras curam,

Alegram

E também machucam

Se mal colocadas!

Precisamos cuidar de nossas palavras

Para que os sentimentos

Não perturbem nossos sonhos

E nosso caminhar.

Prossigo minha pesquisa

Ora sonhando

Ora acordada

Mirando seres sagrados

E buscando sabedoria e tranquilidade

Para seguir poetizando meu silêncio

Múltiplo e profuso.

A certeza a cada novo amanhecer

De mais harmonia

De mais alegria

Entre os seres

Entre o visível e o invisível

Entre o indivisível que habita

Na terra e no mar.

É preciso calar,

É preciso amar,

É preciso sentir mais,

É preciso ser a gente mesmo

A cada instante,

A cada suspiro de nosso viver.

Vai caminhante antes do dia nascer,

Vai caminhante antes dos sonhos

A noite tecer…

Arte de Fabiano Kuaray

Arte de Fabiano Kuaray

Para os humanos, a palavra, esse código ancestral comunica pensamentos e constrói pontes entre os mundos. Há muitos e muitos séculos, cantamos, rezamos, pronunciamos e sopramos mensagens de transformação.

Saber se colocar, entrar e sair de todos os lugares é uma ética para se dispor a conviver com a diversidade de seres que pensam e anseiam alcançar a sensível sabedoria de sentir sua própria sombra.

Disputas ideológicas muitas vezes causam atritos e podem afastar a energia que construímos e nomeamos como amizade, respeito e troca de conhecimento.

Refazer ou reconstruir a teia das relações nos exige uma capacidade de compreender a imperfeição que habita em nossa humanidade, tão machucada pelas contradições do dia a dia.

Quando compreendermos que o amor é uma partícula invisível que une e nos faz enxergar a nós mesmos, entenderemos que nada, ninguém e nenhuma palavra mal soprada poderá acabar com uma amizade verdadeira.

11/06/2024

EU NÃO SABIA QUE ERA TÃO BONITO – por Veronica Pinheiro

“A GENTE PRECISA APRENDER A SE ENVOLVER COM A TERRA, COM OS NOSSOS RIOS, FLORESTAS E MONTANHAS.

Envolver não significa essa bobagem de interesse privado de ser dono daquele rio.”

Ailton Krenak¹

Choveu tanto na tarde e na noite do dia 04 de junho na cidade do Rio de Janeiro que perdi a conta das pessoas que mandaram mensagem perguntando se a visita ao Pão de Açúcar, dia 05 de junho, seria cancelada. Chegamos à segunda imersão do Percurso Aprendizagens: o encontro das crianças com as águas da Baía de Guanabara. Quando confirmado o encontro, não havia previsão de chuvas para o dia do passeio. A previsão mudou, mas optei por confiar nas águas e no Sol. O encontro não foi desmarcado. Saí de casa com muita chuva. Chegamos à escola para encontrar as crianças debaixo de chuva. No entanto, optei por confiar nas águas e no Sol.

Tania e Ericka, companheiras de sonhos e Sol, foram direto para o local de visita. “Veronica, aqui não chove. Muitas nuvens.” “Diga ao Sol que contamos com ele. Diga a ele que as crianças já já sairão da escola”. Café da manhã servido na escola, era hora de embarcar no ônibus rosa e reencontrar nosso gentil motorista.

Um acordo não palavrado ficou firmado na Favela da Pedreira: Se o ônibus rosa está presente, as crianças vão passear; logo é preciso que elas saiam e retornem à favela com tranquilidade. Os caminhos que levam à escola são desobstruídos para que nosso ônibus passe, somos observados do embarque até a saída do complexo. As crianças não percebem que a comunidade de alguma forma também muda sua rotina para que elas vivam dias de alegrias. Me comoveu ver que a comunidade e o poder paralelo se preocupa com o bem-estar das crianças e professores.

Saímos da escola. Não chovia mais. “Vamos subir e ver nuvens; com o tempo nublado não dará pra ver nada.” Ouvi, não respondi, pois confiava nas águas e no Sol. A caminho do Pão de Açúcar, passamos pelo Rio Acari. Nosso rio querido, que corta toda região da escola. Um rio largo que nos ouve. Um rio testemunha da vida e do terror imposto à região. Um rio que ainda guarda seus encantos, jacarés e capivaras. O Rio Acari é um dos maiores cursos de água do Rio de Janeiro, ele é o motivo do nosso passeio². Acari é tão forte que macrobiologicamente resistiu até pouco tempo. Nos despedimos do rio e seguimos viagem. Percorremos 40 km até o Pão de Açúcar. Subimos o Morro da Urca e o Morro do Pão de Açúcar para observar de cima as águas da Baía de Guanabara.

Durante a vivência, as águas e o Sol nos receberam como quem recebe parentes queridos. Não chovia, as nuvens se recolheram num outro lugar para que pudéssemos contemplar tudo quanto se era possível ver das alturas. O Sol nos guardou na subida e descida dos morros, seu brilho refletido nas águas encantou todo grupo. Foi a primeira vez que não vi medo nos olhos das crianças. As crianças se abraçavam e andavam de mão dadas. Sorriam sorrisos largos e duradouros. Tinha hora que eu jurava que via os sorrisos delas refletidos no mar. Algumas choraram. Duas choraram muito e não sabiam dizer exatamente o porquê. Ao contrário dos sorrisos, os choros eram curtos e breves. Tenho certeza de que era só o mar que mora dentro do peito e que não quis se conter.

Éramos 10 adultos no passeio, e lá entendi que não haveria mediação. Cada adulto tinha 4 crianças para acompanhar. Andávamos bem próximos, era dia de festa. Eu pouco falei, a natureza não carece de mediador. As águas, o Sol, as Plantas, os Pássaros, os Micos, o Vento falavam tanto, tanto, que me assustei com tamanha receptividade. Tudo chamava muita atenção das crianças, os aviões que pousavam bem na nossa frente, os turistas falando inglês, as plaquinhas que um amigo lia para o outro que não sabia ler. “Tá escrito que a baleia vai passar aqui até setembro” “Jura! É hoje? Lê direito e veja se tem dia.” A baleia não passou no dia 05 de junho.

Muita coisa foi curada em nós naquele dia. Há quem tenha horror em ouvir que a educação pode curar. Aprendi com os mais velhos quilombolas e indígenas que tudo pode ser cura: cantos, palavras, comidas, abraços, conselhos. Quando estávamos nos encaminhando para descer, um helicóptero pousou no heliponto do Pão de Açúcar.

“Tia, o que o helicóptero quer?”

“Ele não quer nada, meu filho.”

“Tia é tiro?”

“Não. São pessoas passeando, elas entram no helicóptero para passear e ver toda cidade de cima.”

O menino de 11 anos só conhecia o helicóptero no contexto da guerra urbana. A polícia no Rio de Janeiro tem uma frota de helicópteros. As aeronaves blindadas são utilizadas em operações policiais, e os meninos sabem que quando tem helicóptero é que a situação está pior que o habitual. O helicóptero da reportagem eles também conheciam. Mas helicóptero de passeio? De passeio, não. Isso porque a cidade separa. A cidade tem muros rígidos para excluir muitos e guardar alguns. O capitalismo determina os significados que os signos terão dentro de uma mesma cidade: para meu aluno, helicóptero significa perigo; para turistas, diversão.

“Mas a minha observação sobre as cidades é que elas funcionam como um verdadeiro sumidouro de energia.” Ailton Krenak

“Tia, então a gente tá na Europa?”

A pergunta me doeu o peito, não pelo desconhecimento geográfico. Mas por esse menino entender que não faz parte daquele Rio de Janeiro. Porém era dia de festas e encontros de vida. Mais uma vez a vida presente na natureza, a mesma vida natureza que sustenta o menino, nos abraçou novamente. Suspensos no ar, dentro do teleférico éramos só gente, ar, montanha, água, pássaros, Sol e água. O mesmo menino chorou abraçado à diretora da escola. Ele me disse que não vai esquecer de cuidar da natureza.“Tia, eu não sabia que era tão bonito.” “Você é natureza, igualzinho a essas montanhas e as águas da baía.”

Esse passeio inaugurou um outro movimento de conversas sobre a vida das pessoas e sobre a vida dos rios na escola.

Ahh, quando descemos do bondinho, as nuvens recobriram os céus naquele lugar. Pedi a chuva para esperar a gente voltar pra casa. Ela nos ouviu.

Quando foi transferido o sentido da vida para ter coisas, a gente já começou a se afastar da Mãe Terra. Essa mãe maravilhosa que chama a atenção da gente, inclusive para falar: “Ei, vocês estão vivos”. Quando uma mãe dá uma bronca dentro de casa, ela não está só dando uma bronca para a gente não estragar a casa, ela está dando uma bronca para dizer: “Vocês estão vivos”. Pra gente não se alienar do sentido de estar vivo. (Ailton Krenak)

Photos: Ericka Hoch

__________________

¹ “Trocamos nossa humanidade por coisas.” https://revistatrip.uol.com.br/trip-fm/ailton-krenak-trocamos-nossa-humanidade-por-coisas

² “Cadê o rio que estava aqui?” https://selvagemciclo.com.br/diario-de-aprendizagens/#tab-1717677150043-1

06/06/2024

ANDAR COM CONSCIÊNCIA – por Cris Takuá

Arte: Fabiano Kuaray

Arte: Fabiano Kuaray

Ero Tori (Façam surgir a consciência)

Ero Tori Tori

Ero Ta kua (Façam alcançar o som do conhecimento )

Ero Ta kua ta kua….

Quando sentimos os ensinamentos transmitidos pelos mestres e mestras do saber, percebemos que somos direcionados a aprender a nos colocar no mundo, na relação com tudo e com todos que nos rodeiam. Todos os seres possuem uma profunda interação com a grande teia da vida, desde que desabrocham nesse mundo. Nós, humanos, somos seres imperfeitos, mas capazes de uma transformação possível para alcançar o Arandu, a sensível sabedoria de sentir a nossa própria sombra. Mas, para isso, temos que estar dispostos a andar com consciência, andar sentindo o som do conhecimento, que nos possibilita enxergar para além das aparências.

As crianças são seres sensíveis, observam cada sentido das coisas. Tenho observado em muitos momentos as crianças questionando os adultos por suas atitudes contraditórias. Alcançar e andar com consciência compreende superar a contradição nas ações diárias. Sinto e vejo abelhas, formigas, cachorros, galinhas e tartarugas com sensibilidades e ações conscientes muito mais equilibradas do que a de muitos humanos.

O grande mistério da vida está em atravessar o portal do que os nossos olhos nos possibilitam ver e mergulhar no infinito mundo das redes de conexões dos saberes e fazeres que são os códigos de acesso ao entendimento. Durante os muitos anos em que dei aula numa escola, insistentemente eu sempre cutucava meus alunos para sentirem e estarem atentos à consciência ao caminhar, ao falar e ao se manifestar no mundo. Nem sempre eu era compreendida por eles ou por algumas lideranças, que sempre achavam que eu estava querendo falar de política. Uai? Política?

O que será a política do nosso próprio terreiro senão a de respeitar todas as formas de vida? As montanhas, os rios, as formigas e as cotias. Semear a micropolítica é algo muito encantado, porém desafiador. São séculos de deterioração do Teko Porã, a boa e bela maneira de Ser e Estar num território. Andar com consciência compreende se permitir a praticar essa delicada e sofisticada tecnologia ancestral, o Bem Viver.

Foto: Anna Dantes

Foto: Anna Dantes

Desde que saí/fui tirada da sala de aula formal, curiosamente, por todos os lugares em que tenho caminhado, me encontro com crianças, em oficinas, rodas de conversa e vivências. E escutando e percebendo o modo como elas concebem a relação das coisas, me surpreendo com a capacidade que as crianças têm de andar com consciência, de sentir o som de tudo que as rodeia.

Criança deveria ser liderança nesse mundo de tantos humanos desmemorizados e sem consciência!

Séculos se passaram e a nossa humanidade escravizou plantas, peixes e montanhas em nome de uma razão delirante, que passou a julgar e comprar/descartar tudo que não corresponde ao padrão estabelecido. Preocupados com o desenvolvimento, a ordem e o progresso, adultos humanos criam leis e fazem guerras.

Enquanto isso, crianças em todo o mundo estão a observar esse descompasso e a se posicionar perante a ética que permeia nossos envolvimentos com a vida e não o desenvolvimento dos seres viventes.

Qual a ética que envolve suas relações no dia a dia?

Para andar com consciência e alcançar o som do entendimento das coisas devemos silenciar e escutar mais as crianças.

Foto: Vhera Poty

Foto: Vhera Poty

04/06/2024

ESSA SEMANA NÃO RECEBI BILHETES – por Veronica Pinheiro

A escola está fechada. Hoje não tem foto. Essa semana não vi as crianças. A escola está fechada. O acesso está mais difícil que o comum. “Usem crachá”. “Esperem antes de sair de casa”. Não saia de casa!

Alternamos entre semanas de encantamentos, euforia, alegrias e medo. Perigo difuso. Perigo concreto. Esta semana não recebi bilhetinhos, nem abraços de braços curtos.

Essa semana me lembrou meus primeiros dias na escola. Na ocasião, a sala de leitura ainda não podia ser usada. Em uma caixa colorida, eu colocava os livros que leria com as turmas em sala de aula. Levava na caixa livros para todas as crianças. Onde eu estivesse com aquela caixa, lá estava a sala de leitura. Era um exercício, meu e das crianças, de transformar o lugar. A mágica sempre estará no encontro. Formada a roda de leitura, a gente podia estar e ser o que bem quisesse.

No primeiro mês de aula, lemos juntos Manu e Mila, de André Alves. Numa turma do 3º ano do Ensino Fundamental, distribuí os livros para crianças de 7 e 8 anos de idade. Alfabetizadas em português, ou não, todas recebem um exemplar do livro. Se tem uma coisa que criança que não lê faz com facilidade é imaginar. Enquanto não somos obrigados a enquadrar o que pensamos, sonhamos e sentimos sem regras gramaticais, confiamos no repertório interno com muita força. O repertório interno é todo um mundo que a criança traz de casa – as brincadeiras, as crenças, os saberes, os sabores. A escola regular, em muitos momentos, ignora a vida vivida pelas crianças e trabalha para que elas façam o que a Base Comum Curricular espera delas.

Quando entrego livros nas mãos das crianças, digo que, mesmo que elas não entendam as palavras, podem ler cores, desenhos, símbolos e traços. Elas podem também fingir que estão lendo. Podem inclusive fechar os olhos e dormir enquanto eu leio. Antes que alguém julgue absurda a permissão que dou às crianças, trago uma informação: alguns alunos moram em locais onde acontecem bailes e festas que começam às 21h de um dia e terminam às 8h da manhã do outro dia.

Antes de iniciar a leitura digo tudo o que pode. Num ambiente que se especializou em dizer o que não pode, poder é subversão. Lemos em voz alta e com brilho nos olhos Mila e Manu, a história de dois amigos que procuravam a “ALEGRIA”. Foi uma leitura delicada que plantou pensamentos bonitos nas crianças e em mim. Durante a leitura, recebi dos gestores da unidade uma notificação de perigo e que as crianças não poderiam sair das salas. Corredores e banheiros são nossos lugares mais vulneráveis. Lembro de terminarmos a história deitados no chão da sala porque o tiroteio estava muito perto. Lembro de compartilhar um cuidado que eu não sabia que era capaz de compartilhar. Lembro de desejar de todo coração nunca mais ver as crianças deitadas no chão para se proteger de tiros.

Lembro também de passar 2h em absoluto silêncio ao chegar em casa; era um silêncio da boca pra fora porque dentro existia uma barulheira de causar medo. Fazia tempo que eu não sentia medo. Medo por mim, que saí da zona de perigo. Medo pelas crianças que dormiriam lá.

Quatro meses depois desse episódio, recebemos orientações para ficarmos em casa. Apenas um dia na semana a escola abriu, mas as crianças não apareceram. Eu estava lá com tintas, livros e uma fogueira artificial. Comprei uma fogueirinha de LED que simula chamas reais. Uma tentativa de aquecer os corações gelados de medo. Mas as crianças não estavam lá. Sentada à beira da fogueira de faz de conta, ouvi a voz de uma professora que pouco fala comigo. Ela entendeu o convite, conversamos a manhã inteira, ela me contou de suas turmas e trajetória em escolas. Descobrimos, por conta da fogueira, que temos muitos sonhos em comum. De alguma forma, nos aquecemos uma à outra… Saí da favela cantando um samba antigo de seu Nelson Cavaquinho. O mesmo samba que eu cantava quando eu era jovem e voltava tarde da universidade. Eu cantava para espantar o medo de subir sozinha o morro onde eu morava. Cantava para aquecer o coração e espantar o medo, assim meu avô ensinou. No último dia de escola aberta, cantei para sair da escola.

“Quando eu piso em folhas secas

Caídas de uma mangueira

Penso na minha escola

E nos poetas da minha estação primeira

Não sei quantas vezes

Subi o morro cantando

Sempre o Sol me queimando

E assim vou me acabando

Quando o tempo avisar

Que eu não posso mais cantar

Sei que vou sentir saudade

Ao lado do meu violão

E da minha mocidade”

Enquanto escrevo, recebi a mensagem que podemos retornar. Que sejam bons os dias que virão.

Awrê

30/05/2024

AVÓZINHA DO MUNDO: ARAUCÁRIA – por Cris Takuá

Hoje sonhei com a avózinha das florestas

A grandiosa mestra

Conhecedora dos sábios segredos

Da ciência das ciências dos mistérios.

Em poucas palavras ela foi me tecendo

Pensamentos, me revelando caminhos

Me orientando e mostrando a

Incrível delicadeza que habita

Na simplicidade das coisas.

Meu espírito voou e percorreu

Vales e montanhas

Bailou, rodopiou e sentiu

A profunda liberdade que reside

Na morada sagrada dos espíritos secretos.

Não há saber maior que o Amor!

A cada dia nos surpreendemos

Com as revelações que surgem

No novo amanhecer

Na noite fria mergulhei em busca de entendimento

E pra minha surpresa,

A grande mestra lá estava

Em seu trono sagrado sentada

A me esperar

Nas longas caudas de uma Araucária

Com sua flauta e seu Maracá

Só me aguardando pra junto a ela

Prosseguir com a cantiga

E soprar poesias para os quatro cantos

A fim de colorir e massagear

Os seres dessa Terra!

Cansados e sofridos

Pela falta de entendimento.

Oh seres caminhantes, despertai-vos

Desse sono profundo

E sentis a saborosa magia

Que mora no silêncio cantante

Dos pensamentos seus!!!!

Foto: Carlos Papa Tekoa Yvyty Porã, RS

Foto: Carlos Papa Tekoa Yvyty Porã, RS

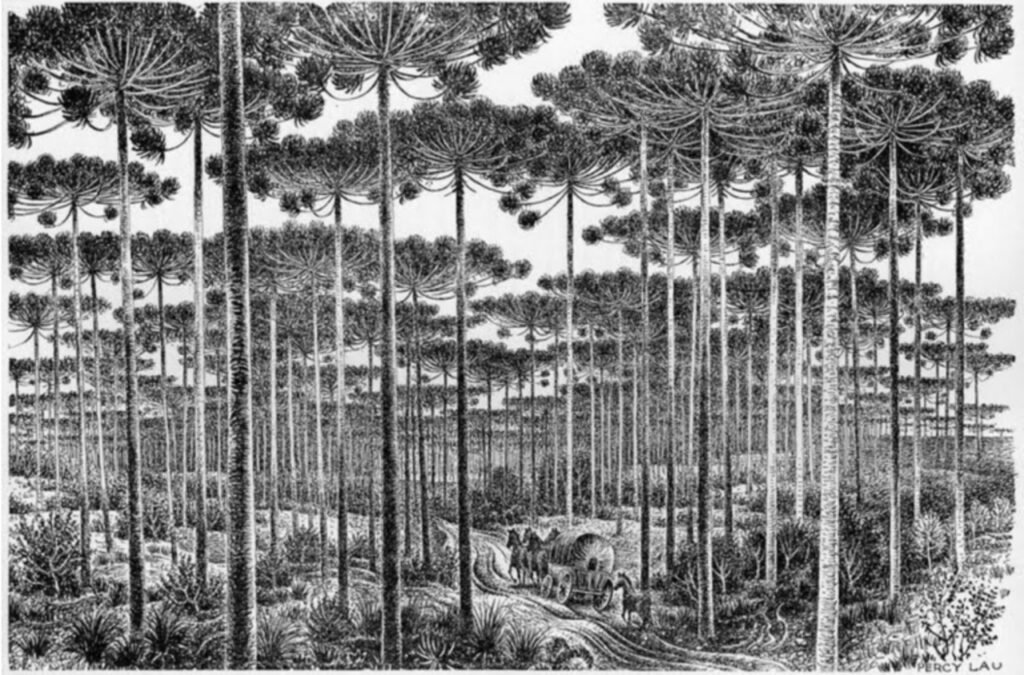

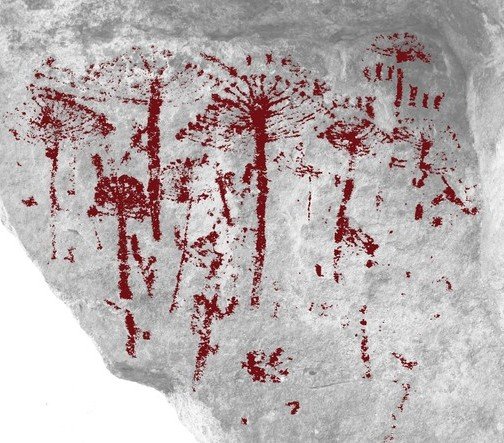

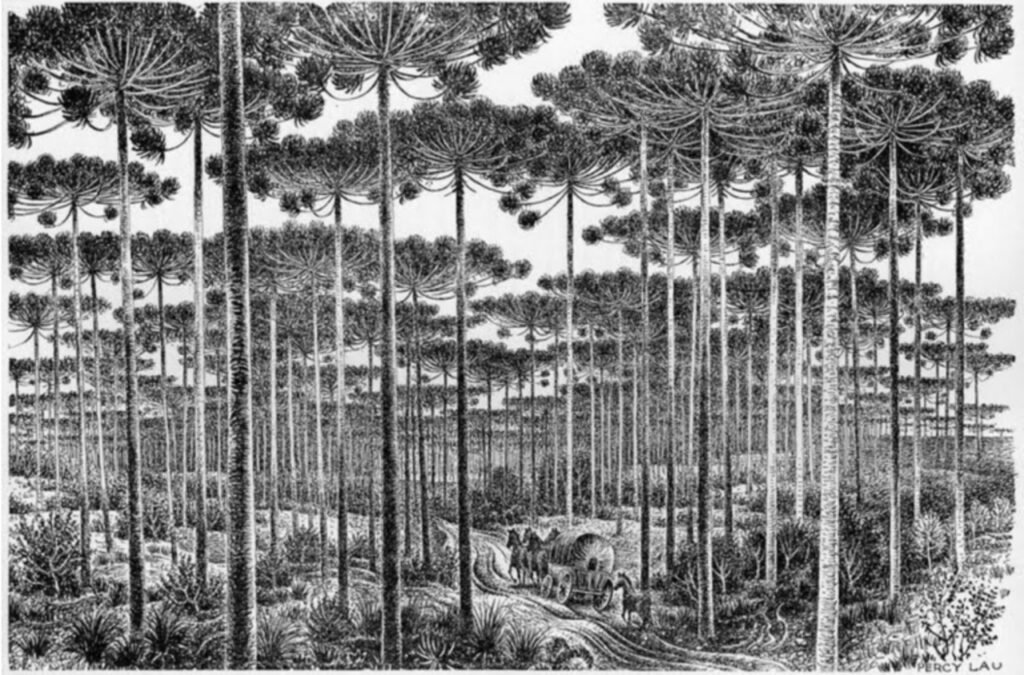

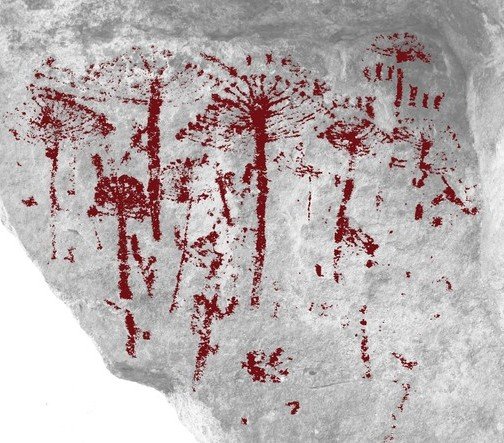

Há milhares e milhares de tempos surgiu esse ser sagrado Kuri, como chamam os Guarani a araucária. Essa árvore tão antiga é uma avózinha vegetal do mundo. Registros arqueológicos mostram sua existência e resistência há muitos séculos. Nesses tempos todos, as araucárias já presenciaram muita luta, resistência e também muita beleza; uma memória ativa que, lá do alto de suas verdes copas, presenciam.

Nas últimas semanas estamos presenciando no Rio Grande do Sul um profundo desequilíbrio atingindo a vida de seres humanos e não humanos. O transbordamento do Rio Guaíba, do Rio Taquari e de tantos rios que, machucados pelas duras ações humanas, não aguentaram a pressão da chuva grande e inundaram, destruíram e deixaram seu recado.

The Ija kuery, guardiões de tudo que habita nessa Terra, estão cansados dos seres humanos, imperfeitos e desajustados. Há muito tempo estão a observar as pegadas tão pesadas do agronegócio, da mineração, do desamor e do desrespeito para com a diversidade das formas de vida.

Gravura a bico de pena por Percy Lau, Arequipa, 1903

Gravura a bico de pena por Percy Lau, Arequipa, 1903

Rio de Janeiro, 1972. Fonte: Tipos e Aspectos do Brasil IBGE 1966

O marco temporal, essa tese anticonstitucional, que permite a revisão e o abuso das terras indígenas já demarcadas, é o ápice da ignorância e do abuso humano, que não consegue enxergar que sem floresta viva não haverá vida possível. A luta e o rezo constantes para garantir e proteger os territórios ancestrais dos povos indígenas são justamente para que todas as formas de vida possam viver: araucárias, cotias, pacas, abelhas, ametistas, montanhas, rios e peixes.

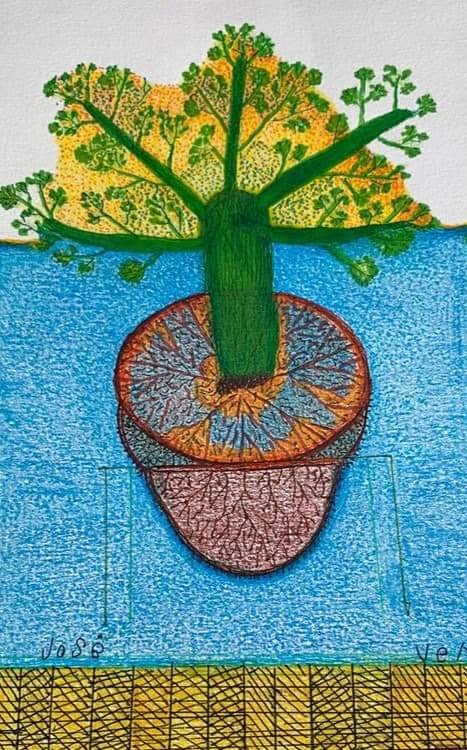

Há duas noites, concentrada na Opy’i, casa de reza, em diálogo e estudo com plantas professoras, o espírito da Kuri veio falar comigo. Ela era bem velha e grande. Me disse calmamente que está lá do alto assistindo a toda a confusão e sofrimento que está acontecendo. Viu muitos parentes vegetais, animais morrendo afogados, arrastados pela lama, pela água brava e nada pôde fazer. Ela somente assistiu, silenciosamente, com seus bracinhos como se estivessem em forma de saudação, que reverencia todos os dias o sol, a lua e a vida, pedindo força e proteção. Ela ficou um tempo me mostrando as grandes florestas que já existiram de araucárias e que hoje estão reduzidas a algumas. Me mostrou também a força do petyngua, cachimbo Guarani feito do nó do pinho dela, e o quanto cada um que o carrega consigo deve respeitá-lo. Me recordou imagens muito belas de mulheres, preparando farinha de pinhão com seus pilões, cenas antigas onde tudo era profundamente interligado. Aos poucos as imagens e a voz dela foram desaparecendo e fui aos poucos voltando e, ao olhar para o fogo, que estava intensamente vivo, senti de me levantar e compartilhar com os jovens que comigo estavam aquela experiência mágica e muito proveitosa que havia sentido, presenciado e aprendido mergulhada em profundas mirações.

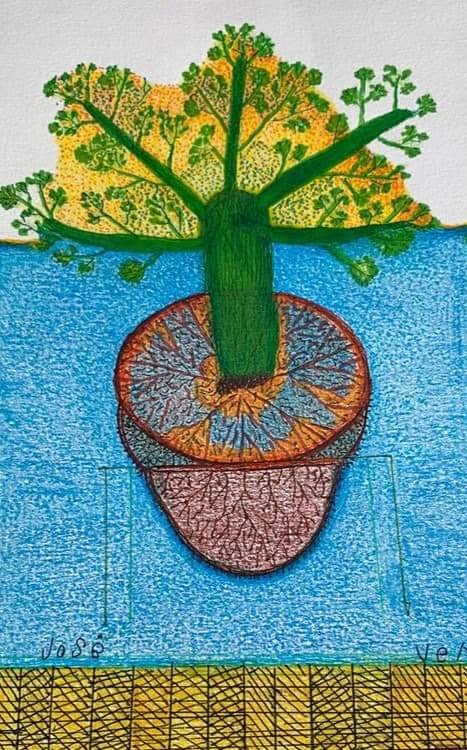

Pintura: Jose Vera, RS

Pintura: Jose Vera, RS

Ao amanhecer do dia refletindo sobre toda a noite de estudos e aprendizados, me recordei de passagens do livro a “Queda do Céu” de Davi Kopenawa….

“No começo a terra dos antigos brancos era parecida com a nossa. Lá eram tão poucos quanto nós agora na floresta. Mas seu pensamento foi se perdendo cada vez mais numa trilha escura e emaranhada. Seus antepassados mais sábios, a quem Omama criou e a quem deu suas palavras, morreram. Depois disso, seus filhos e netos tiveram muitos filhos. Começaram a rejeitar os dizeres de seus antigos como se fossem mentiras e foram aos poucos se esquecendo deles. Derrubaram toda a floresta de sua terra para fazer roças cada vez maiores. Omama tinha ensinado a seus pais o uso de algumas ferramentas metálicas. Mas já não se satisfaziam mais com isso. Puseram-se a desejar o metal mais sólido e mais cortante, que ele tinha escondido embaixo da terra e das águas. Aí começaram a arrancar os minérios do solo com voracidade. Construíram fábricas para cozê-los e fabricar mercadorias em grande quantidade. Então, seu pensamento cravou-se nelas e eles se apaixonaram por esses objetos como se fossem belas mulheres. Isso os fez esquecer a beleza da floresta. Pensaram: “Nossas mãos são mesmo habilidosas para fazer coisas! Só nós somos tão engenhosos! Somos mesmo o povo da mercadoria! Podemos ficar cada vez mais numerosos sem nunca passar necessidade! Vamos criar também peles de papel para trocar!”. Então fizeram o papel do dinheiro proliferar por toda parte, assim como as panelas e as caixas de metal, os facões e os machados, facas e tesouras, motores e rádios, espingardas, roupas e telhas de metal. Eles também capturaram a luz dos raios que caem sobre a terra. Ficaram muito satisfeitos consigo mesmos. Visitando uns aos outros em suas cidades, todos os brancos acabaram por imitar o mesmo jeito. E assim as palavras das mercadorias e do dinheiro se espalharam por toda a terra dos seus ancestrais. É o meu pensamento. Por quererem possuir todas as mercadorias, foram tomados de um desejo desmedido. Seu pensamento se esfumaçou e foi invadido pela noite.”

(Davi Kopenawa, “Paixão pela mercadoria”, em A Queda do Céu)

Pintura rupestre de Araucária, Pirai do Sul, PR

Pintura rupestre de Araucária, Pirai do Sul, PR

28/05/2024

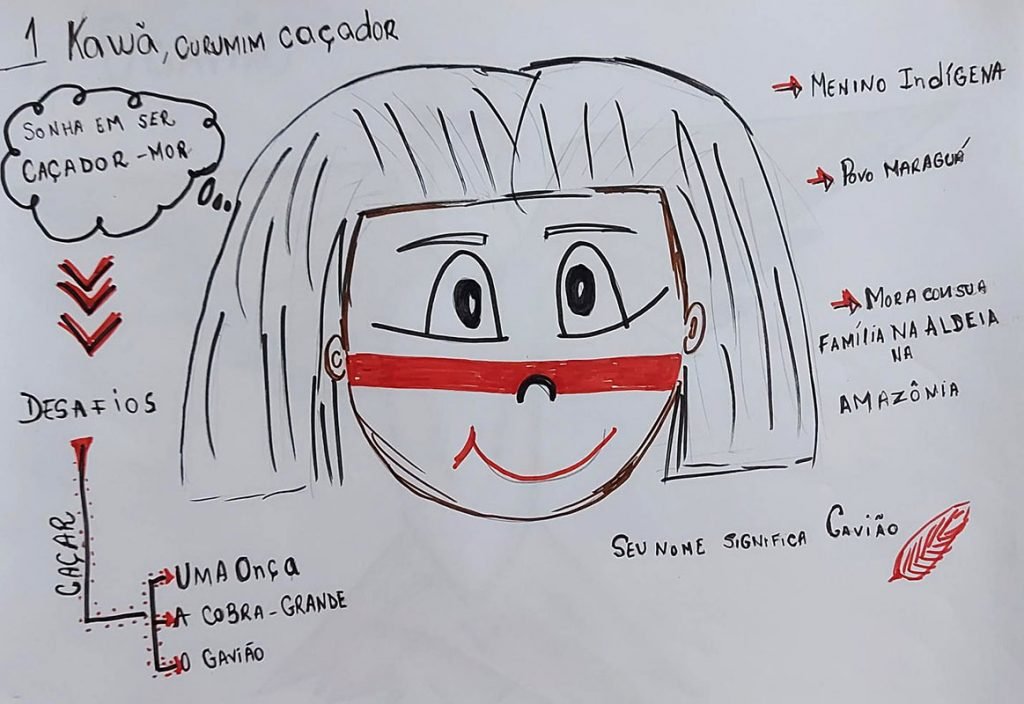

LER A TERRA – por Veronica Pinheiro

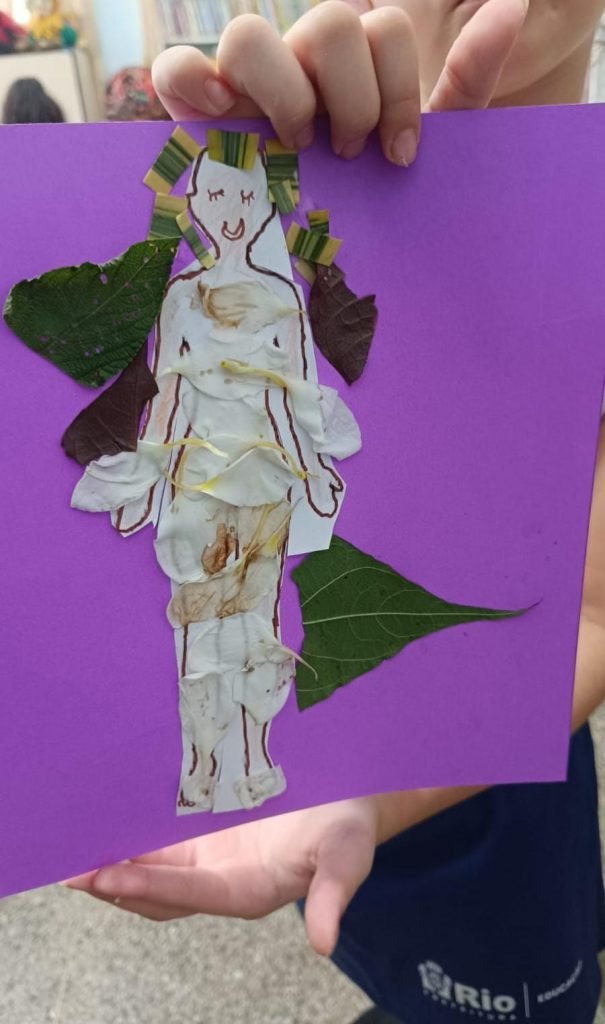

Me lembro da conversa que tivemos com o barro no encontro Cosmovisões da floresta, no dia 13 de maio de 2023, no Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro (MAM-Rio). O encontro entrelaçou os projetos Ore ypy rã – Tempo de Origem e o Selvagem em um dia de exposição e atividades com cantos, danças, conversas. Diante de um vaso de cerâmica marajoara, Francy Baniwa começou a falar sobre como as mulheres Baniwa conversam com a argila, que é um ser muito antigo e sagrado. De onde eu venho, o barro também é sagrado. Lembro do barro vermelho que cobria toda a comunidade e de como tocávamos com a mão no chão e no coração antes de dançar ou jogar capoeira. Lá em casa, o barro era nossa avó; berço originário e colo derradeiro. O barro só era colhido mediante as necessidades. Levei isso para as oficinas com argila.

Andando pelo bairro de Costa Barros, onde a escola está localizada, entre barrancos e barracos, a quebrada do terreno ocasionada pela chuva, deslizamento ou pela ação do homem revela as cores guardadas na terra. Texturas e tonalidades de marrom e matizes avermelhadas colorem e revelam propriedades físicas, químicas e mineralógicas do solo. Durante o planejamento das oficinas de plantio das espécies frutíferas da Nhe’ëry com Gerrie Schrik, me foi feita a seguinte pergunta: Como é o solo da escola? Não tendo as respostas técnicas, pude falar com detalhes sobre o que vi. E via as cores da terra nas escavações e barrancos. Olhar pra terra é uma prática que tento passar para as crianças.

“Ninguém fazia análises de solo, conhecíamos o solo só pelo olhar. Só de olhar para a terra já sabíamos o que plantar. Conhecíamos a vegetação. Numa terra que dá muita leguminosa nativa, plantava-se feijão; numa terra que dá muita gramínea nativa, plantava-se milho e arroz. É a linguagem cósmica. É simples. Não é preciso fazer análises de solo porque a terra já diz o que está disposta a oferecer.” Nego Bispo

A terra diz. Passamos na escola uma semana olhando a terra. As crianças e eu. Faixas de terra ao redor da escola que não foram cobertas pelo cimento foram os textos da semana. Em sala, eu e as crianças lemos e conversamos sobre a “Carta da Terra”. Curioso, as crianças nem sabem mais o que é uma carta. Elas escrevem recadinhos em papéis pra mim, mas chamam o bilhete de mensagem. Expliquei o que era uma carta, para que servia e como era composta. “A Terra pode escrever uma carta?”, “Não! ela não tem braços nem mão. Ela deve ter ditado e alguém escreveu: tipo Deus com Moisés”.

Depois de muita conversa, saímos quintal afora. Parecia uma expedição: cadernos, canetas, um galho para apoiar na subida. O livro estava fora da sala de leitura. Lemos o livro mais antigo de todos: lemos a terra. Por um tempo, só observamos as cores do solo; por outros, só os pequenos insetos e animaizinhos que viviam ali sem que ninguém notasse. “Tia, mora muita gente aqui!”, “Eu sei, você acha que a escola só tinha móveis e livros? A escola é habitada por seres vivos mesmo quando nós não estamos nela”. Formigas, lagartos, aranhas, plantas, muitos pássaros. As crianças do 1º ano se espantaram. Elas não sabiam que tantos pássaros diferentes visitavam aquele quintal no final da tarde. Ficamos sentados em silêncio no meio da quadra depois da história contada. Eu disse que eles receberiam visitas. Visitas aladas, coloridas e cantantes. Tive a sensação de serem as mesmas aves que me acordam em casa. Certamente, não são as mesmas aves, mas é bonito pensar que elas me acompanham até a Pedreira.

Tentei conversar com o senhorzinho que está sempre plantando num pedaço de terra no alto do morro. Certamente ele é a pessoa mais adequada para falarmos sobre as oficinas de plantio e de pigmentos de terra. Ele se relaciona diariamente com a terra: eu vejo quando passo às 7h da manhã pelo seu quintal. Numa região com o segundo menor índice de desenvolvimento humano, existe um homem farto de verde. Solo-planta-homem suspensos e escondidos no verde à beira do asfalto. Enquanto a insegurança alimentar diariamente circula entre a população local, o senhor, que não se desconectou da terra, cuida e é cuidado. Marcamos de visitá-lo, pretendemos chegar com uma cesta de delicadezas, e de alguma forma ser gentil com quem gentilmente pisa sobre a terra.

Pretendemos também levar para ele um quadro pintado com tintas preparadas com as terras do território e da escola. E de alguma forma estabelecer ali um diálogo tendo como partida nosso berço comum: a relação com a terra. As oficinas são movimentos iniciais, são sementes. Germinando as sementes, algumas memórias de vida são despertadas. A vida despertada está no território, nas memórias guardadas na terra e adormecidas nos corpos. Ao estabelecermos uma parceria com uma escola de ensino regular, sonhamos com a ideia de escolas vivas em ambientes urbanos e periféricos. Trazemos como proposta o fortalecimento do território, dos saberes e das práticas de vida que lá existem. Nesse movimento, tentamos identificar quem são os guardiões do bem viver; quem são os seres, que em meio a tantas dificuldades impostas, guardam práticas que sustentam cosmologias ancestrais.

Não existe um modelo único de oficina aplicável para toda e qualquer escola e território. Já compartilhamos oficinas de tintas naturais em outros momentos. Para as crianças da escola Escragnolle, partimos da “Carta da Terra” e chegamos aos pigmentos e pinturas. Ao convidá-las a aprender mais sobre o lugar onde elas vivem, ouvi repetidamente as histórias de violência e medo. Perguntei se elas sabiam de onde eram aquelas tintas da oficina. Algumas crianças desconfiaram que a tinta era barro. “Parece tinta, mas tem cheiro de terra”. Perguntei se elas sabiam que a terra da região da escola era uma terra cheia de cores. Perguntei se elas conheciam o senhor gentil que conseguia ter uma forma diferente de ser e viver na favela. As crianças, assim como os pássaros, sabem de muita coisa. Os pequenos me trouxeram o nome e uma possível data de visita ao senhor.

As crianças disseram que não sabiam que era importante conhecer de terra, de plantas e de quintal. Durante a semana as crianças me presentearam com terras, urucum e flores pigmentadas. Presentes de crianças da Pedreira. Talvez os mais bonitos que já recebi na vida.

Agora estamos mapeando os caminhos verdes da favela. As cores da terra do quintal da escola pintam de amarelo e tons de vermelho os mapas da vida da Pedreira.

Fotos: Wagner Clayton

23/05/2024

CORPO – CASA – TERRITÓRIO – por Cris Takuá

Arte de Cris Takuá

Arte de Cris Takuá

Nosso corpo é território

É casa, é morada ancestral

Nossa casa é a floresta

E através dela atravessamos

um cristalino portal

Nosso território é beira do rio,

É montanha e manguezal

Somos o emaranhado de uma teia

de colorido natural.

A floresta pulsa

e os seres sagrados que nela habitam

estão a nos observar em meio ao vendaval

Respeitar os espíritos da floresta

Deveria ser o princípio inicial

das relações de transmissão de saberes

e conhecimentos

desse nosso mundo atual.

Arte de Kaue Karai Tataendy

Arte de Kaue Karai Tataendy

Tecendo mundos vamos aprendendo a nos relacionar com os espaços que nos circundam. Desde a primeira morada que nos acolhe no útero de nossas mães começamos a perceber e a sentir a dimensão dos muitos territórios que habitamos. Nessa grande teia de relações somos concebidos com modos de pensar e existir conectados com uma memória ancestral, um acervo de saberes e fazeres que habita nossos corpos e existe em muitas camadas. O corpo, casa, território, esse mundo de conexões profundas está passando por modificações significativas devido ao processo de mecanização das relações. A inteligência artificial, cada vez mais presente na vida e nas convivências humanas, tem feito com que as ferramentas ancestrais de comunicação, como a telepatia, a intuição e os sonhos fiquem silenciados no dia a dia de muitos seres.

A nossa grande morada, a nossa casa sagrada, é a floresta. E ela não está presente somente dentro da nossa casa, mas nas cachoeiras, nas montanhas, em todos os espaços onde se constitui o tekoa, que é o território onde se vive, onde se planta, onde se cria, onde se brinca, onde se é possível conviver de uma forma coletiva, de uma forma verdadeira. Sinto que todo o nosso corpo, toda a forma como a gente se coloca no mundo, estão sendo chamados para uma transformação, um redirecionamento. Independente das nossas origens, das nossas posições políticas, filosóficas ou epistemológicas, precisamos ter um compromisso ético com a vida e, assim, conseguir equilibrar o sopro de amor que sai das nossas palavras com o compasso dos nossos passos ao caminhar. Esse é o grande desafio que temos que superar para conseguirmos avançar, com coerência e serenidade, sem sermos constantemente contraditórios nas nossas ações.

Arte de Jera Mirim

Arte de Jera Mirim

Ao longo da história, a humanidade se escorou em uma razão que não coloca os outros seres no diálogo. Os humanos criaram, inventaram, modificaram, destruíram o equilíbrio da natureza. E esqueceram de perceber que as formigas, as abelhas, o vento, as montanhas, os rios e todos os seres que habitam aqui neste planeta, seres visíveis e invisíveis, seres, animais, seres vegetais, seres minerais, eles também possuem uma coletividade, uma dinâmica de vida que pulsa dentro desse território que é o grande planeta Terra. Mas nós, humanos, insistimos em querer ser maiores, em querer ser mais pensantes e donos desse mundo todo. E, em nome disso, causamos todo desequilíbrio nessa humanidade que a gente julga e pensa ser.

Não tem como nos dissociarmos da natureza, porque nós somos a natureza e tudo está interligado. Nenhum humano consegue viver e sobreviver se não tiver água para beber, se não tiver um ar puro para respirar. Todo o processo capitalista e colonizador, em muitos lugares no mundo, impôs um modo de ver e pensar o tempo, e isso afetou os processos de transmissão de conhecimento. Há uma monocultura que rege os alimentos, que rege as epistemologias e os processos de cura e doença. Isso precisa ser compreendido de um modo que os indivíduos percebam que nós não somos nada além de um pequeno grão nessa grande teia que relaciona a vida. Quando penso em casa, corpo e território, percebo o quanto nós, humanos, somos dotados de um grande potencial que é a nossa própria mente. O nosso pensamento é capaz de muito desenvolvimento e criatividade, que podemos nós mesmos nos proporcionar ou nos direcionar a aprender.

As formigas, as abelhas e as plantas são seres muito inteligentes, assim como todos os seres minerais. Eles pulsam a cada dia, se transformam e se recompõem. E nós, humanos, estamos constantemente nos dividindo por classes, etnias, cor de pele, classe social. Mas somos todos humanos e fomos colocados todos neste mesmo barco, que é essa morada sagrada, que é essa casa-território onde habitamos e compartilhamos de lutas e sonhos, de expectativas e querências a cada dia. Se habituar a isso e enxergar de uma forma clara e plena é a missão que cada um de nós carrega nessa morada territorial. Com as nossas sensibilidades, com nossas especificidades culturais, espirituais, somos capazes de alcançar essa grande coletividade que habita a casa planeta Terra, e assim reativar o cuidado e a atenção com o nosso próprio corpo, com a nossa mente e espírito.

Arte de Alexandre Wera Popygua

Arte de Alexandre Wera Popygua

21/05/2024

SERÃO PERMITIDAS APROPRIAÇÕES E RELEITURAS – por Veronica Pinheiro

“Não tenho nenhuma perspectiva com relação a um novo mundo. Eu não acredito num novo mundo. Eu acredito que nós vamos ter que resolver o que a gente vai fazer com este que a gente está estragando. A ideia de um novo mundo está dentro de uma lógica que sugere que o meu sapato acabou, eu compro um novo."

Ailton Krenak

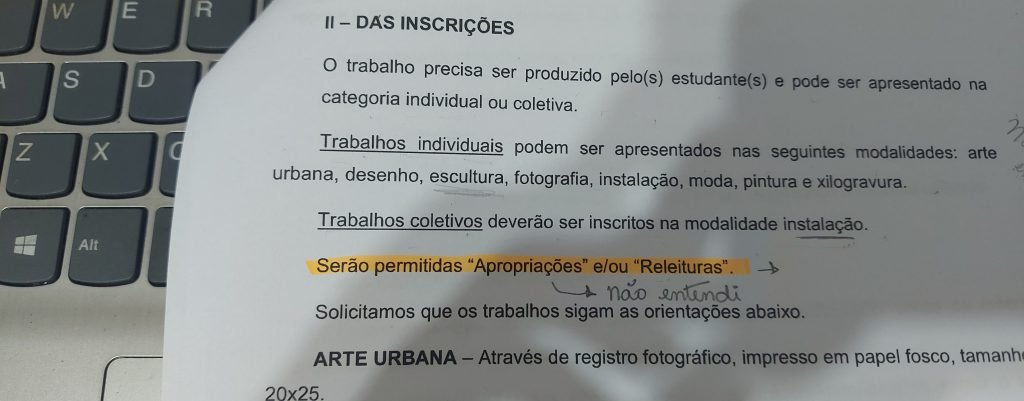

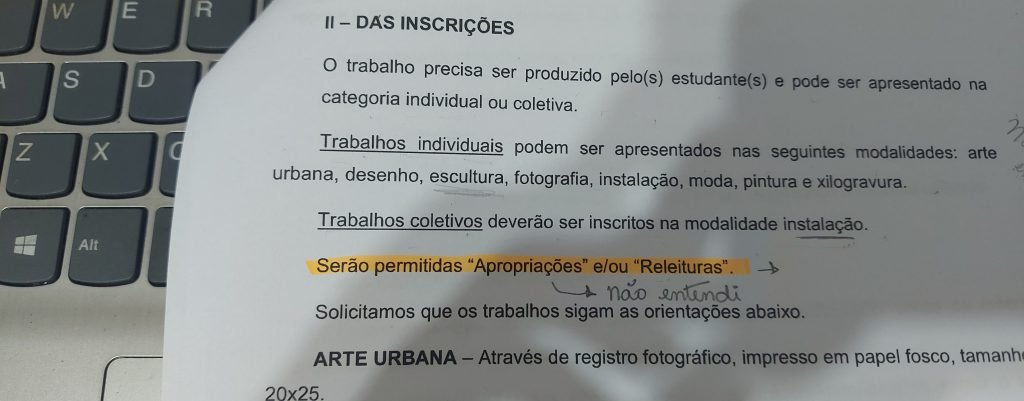

O ano: 2024. As duas reflexões chegaram a mim no mesmo dia: a primeira, um vídeo, do qual transcrevi um trecho da entrevista de Ailton Krenak; a segunda, um edital da Mostra Municipal de Multilinguagens, de onde copiei a frase que intitula este texto.

Esta semana o diário seria sobre a oficina “Cores e terra – pigmentos e pintura”. Porém, no último dia da semana, ainda em expediente, recebi o edital da 4ª Mostra Municipal de Multilinguagens. Minha tarefa era entender como poderíamos inscrever a escola e os trabalhos que estamos desenvolvendo na mostra. Não sei vocês, mas eu leio editais e me atento às miudezas e aos detalhes. Eram tantas orientações pedagógicas somadas a um punhado de siglas e objetivos gerais e específicos. Assumo aqui que sou cismada com leis, diretrizes e pedagogias. As práticas, o não dito, o estabelecido, as escolhas e o fôlego das propostas me interessam mais. A princípio, li para entender em qual linguagem artístico-pedagógica poderíamos inscrever a escola (dança, teatro, música e/ou artes visuais). Depois não consegui parar de pensar sobre o que li.

O tema da mostra – Brasil e seus brasis, a influência dos povos originários na formação da nossa identidade cultural brasileira, à luz da Lei 11.645¹ – tem uma série de agendas a cumprir. Era tanta demanda bonita (competências para o século XXI²; conjugar os 4Cs³; trabalhar temas transversais⁴; incluir a questão sócio ambiental e os Objetivos de Desenvolvimento Sustentável – ODS⁵; ampliar visão de sociedade e de mundo; focar na Agenda 2030 com a Coordenadoria de Diversidade⁶; não esquecer da Base Comum Curricular – BNCC⁷; implementar a Lei 11.645) que até fiquei tonta.

Este texto poderia ter parado no título. Entretanto, convido a todos a pensar em como a gente vai resolver este mundo que estamos estragando. “Serão permitidas ‘apropriações’ e ou releituras’”. Esta frase me saltou aos olhos, automaticamente disse: “não entendi”. Ou entendi tudo. A sentença (frase ou oração; intencionalmente escolho a palavra SENTENÇA) escrita na página 15 do edital diz tanto sobre as relações étnico-raciais propostas pelas instituições e suas escolhas pedagógicas. Porém as instituições são compostas e representadas por pessoas. E como pessoas podemos juntos pensar em possibilidades para reescrever perspectivas e realidades.

Não há neutralidade num texto. Aprendi estudando linguística que em cada signo “dorme um monstro”. Se me atento ao não dito, como ignorar o dito? O escrito?

“O corpo de um negro ou de um índigena está impregnado de cultura e memória, traz as marcas de dor e sofrimento que a colonização impingiu. Essas peles não são fantasias. Portanto, apropriação cultural não é homenagem, é violência simbólica exercida de forma sutil ou explícita. Ninguém tem o direito de usar um cocar e pintar a cara enquanto apoia o genocídio indígena. Um branco não pode cantar samba e continuar destilando racismo.”⁸

Certamente alguém vai tentar explicar e apresentar contextos para justificar a sentença que tanto me doeu os olhos. Pode até explicar, mas quem valoriza documentos e papéis não sou eu. Meu povo guarda memórias e saberes em cantos, em práticas e em rezos. Não sou eu quem exige que tratados e acordos sejam validados por escrito e protocolados. São as instituições. São as instituições que dizem “vale o que está escrito”. E estava escrito:

“Serão permitidas ‘apropriações’”

E se está escrito pode ser reescrito. Que possamos, a partir de 2024, ressecrever coletivamente os caminhos e as possibilidades de coexistência. Toda cultura é resultado de anos de interações sociais e naturais; por isso, a afirmação da identidade é um movimento orgânico. É importante ouvir mais; por exemplo, ouvir como pessoas indígenas gostariam de ser apresentadas e representadas. Muita gente não sabe que um grafismos não é apensas uma pintura; tantas outras, desconhecem que um canto pode trazer memórias antigas e palavras de cura. Que em 2024, possamos entender que a melhor forma de honrar uma tradição é fortalecendo os territórios e respeitando todas as manifestações de vida presentes neles.

²https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000234311

³O conceito dos 4C’s foi apresentado pela associação National Education Association (NEA), em complemento às atividades do “21st Century Skills”, movimento educacional do século 21 que visa capacitar os educadores para avançarem em sua própria prática. Os 4Cs são: pensamento crítico; colaboração; comunicação; criatividade.

⁴ Os temas transversais definidos pelos Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais são: Ética, Pluralidade Cultural, Meio Ambiente, Saúde, Orientação Sexual, Temas Locais. http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/images/implementacao/contextualizacao_temas_contemporaneos.pdf

⁵ São 17 os Objetivos de Desenvolvimento Sustentável (ODS), definidos pelas Nações Unidas. http://portal.mec.gov.br/component/tags/tag/objetivos-de-desenvolvimento-sustentavel

⁷ http://basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/

⁸Apropriação cultural / Rodney William. — São Paulo : Pólen, 2019.

16/05/2024

ENTRE RIOS, MONTANHAS E CRIANÇAS – por Cris Takuá

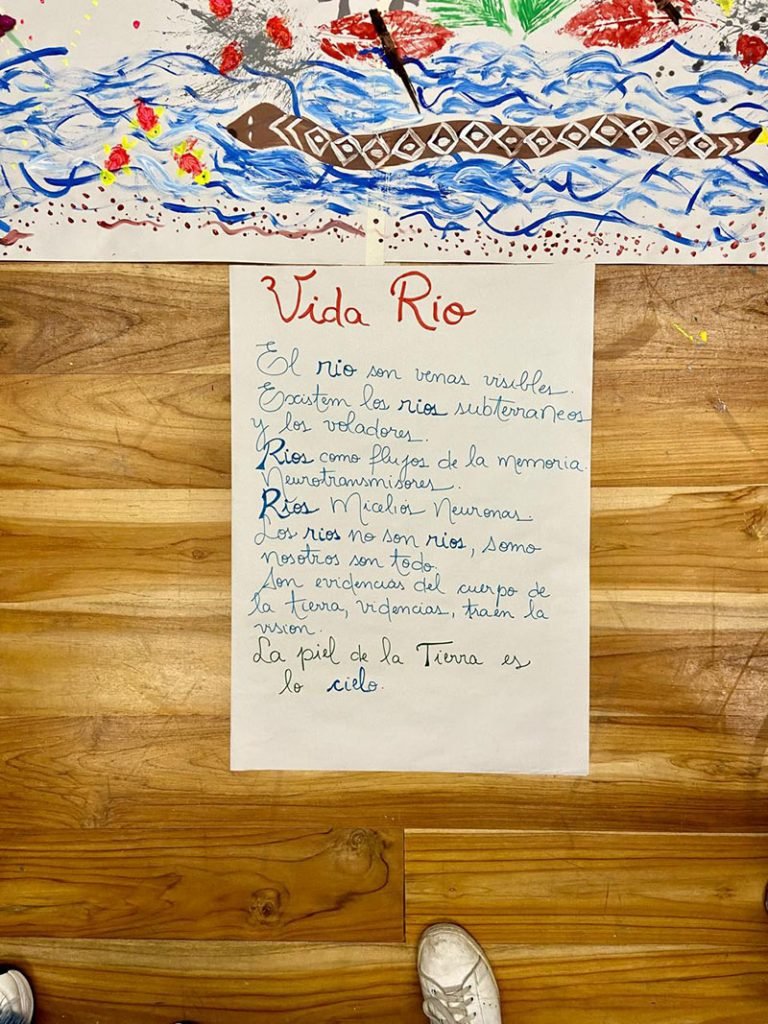

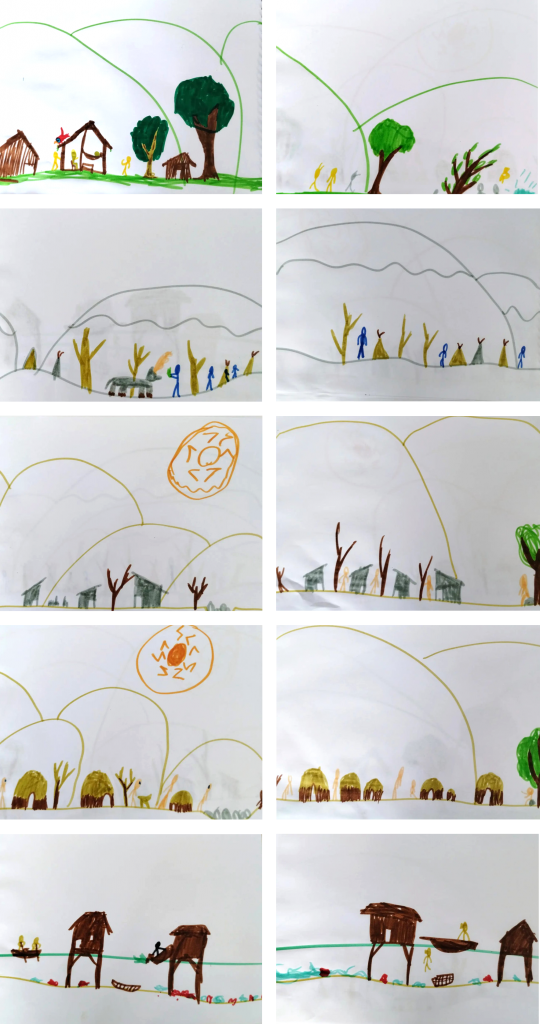

Arte coletiva.

Arte coletiva.

Foto: Cris Takuá

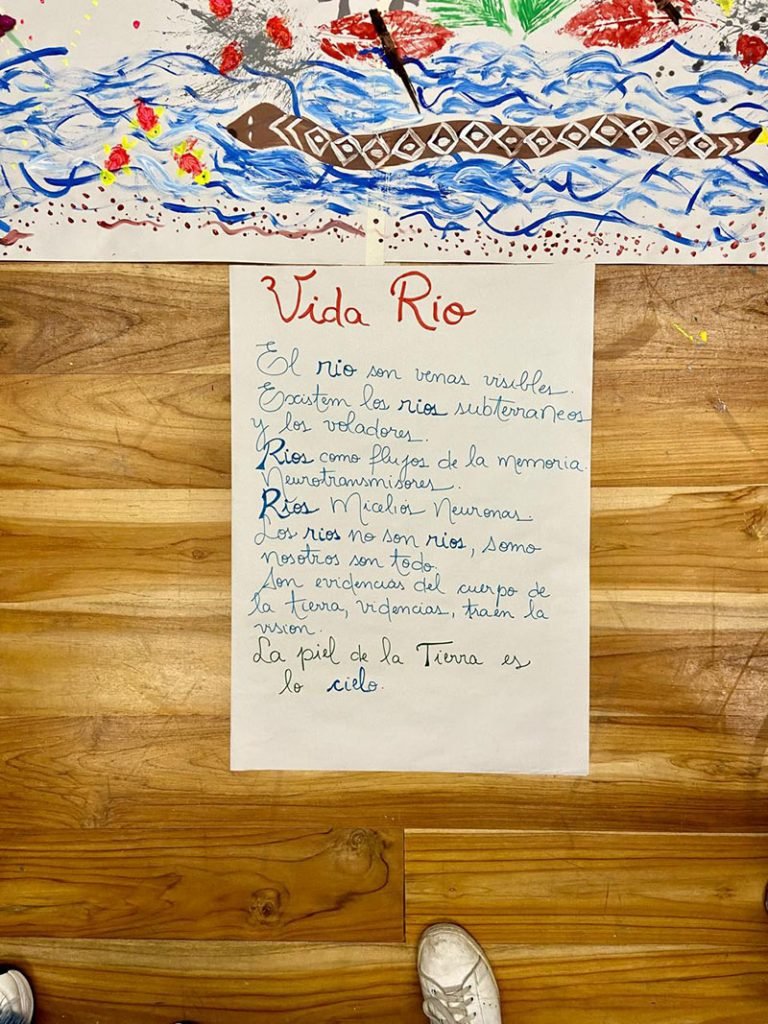

Vida Rios

“ Os Rios são veias visíveis

Existem os Rios subterrâneos

e os Rios voadores.

Rios como flechas da memória

Neurotransmissores

Rios Micélios Neurônios

Os Rios não são Rios, somos nós

São tudo.

São evidências do corpo da Terra

Vidências trazem a visão.

A pele da Terra é o céu.”

*** Anna Dantes, Puerto Berrio,

Colômbia- maio/2024 ***

Residência “Actuar por lo vivo” sobre a bacia do rio Magddalena. Puerto Berio, 3 de maio de 2024.

Residência “Actuar por lo vivo” sobre a bacia do rio Magddalena. Puerto Berio, 3 de maio de 2024.

Foto: Digo Fiães

Os rios são as veias da Terra, são espíritos que caminham serpenteando, deslizando entre pedras e águas cristalinas. Brotam de montanhas antigas e acariciam nossas peles com a possibilidade da vida. Pelos quatro cantos do mundo e ao longo da história, humanos não souberam respeitar a existência dos rios. Mudaram seus percursos, contaminaram seus corpos com dejetos de mineração, agrotóxicos e lixo – muito lixo.

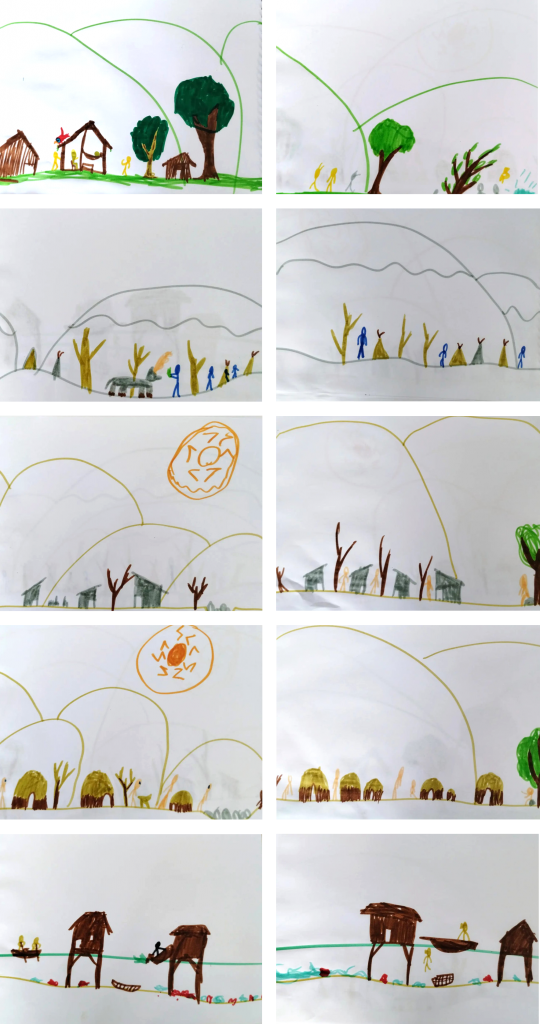

Hoje, crianças estão a refletir e, mais do que isso, estão sentindo as duras consequências dos hematomas nas camadas profundas da Terra. Através de sua sensibilidade estão mediando os conflitos entre os mundos e entre os tempos, com o objetivo de regenerar os vínculos com os seus territórios ancestrais.

Um caminho que vem se desenhando possível é sentir e pensar o rio, diante de todas as suas feridas e complexidades. E assim cantar para o Rio, conversar com ele e escutar suas profundas mensagens. Esses são desafios que seres sensíveis estão conseguindo alcançar.

Fotos: Lina Cuartas e Cris Takuá

Fotos: Lina Cuartas e Cris Takuá

Caminhando nas margens do Rio Madalena em Puerto Berrio, na Colômbia, no início de maio, recordei memórias antigas de crianças brincando e plantinhas brotando nas margens dos rios do mundo. Me conectei com o sagrado Guaíba lá no Rio Grande do Sul, cansado, machucado com toda a confusão humana, e algo ressoou em mim em forma de canção….

Yxyry Porã Mbaraete

Yxyry Porã Mbaraete

Yxyry reo Para Guaxu aguã.

Yxyry reo Para Guaxu aguã.

💦💧🩵💦💧

Um canto para o belo Rio Madalena, Guaíba, Taquari, Rio Doce e Paraopeba.

As montanhas são como avózinhas – nos abraçam e nos protegem. Muitas águas brotam do alto das montanhas, por isso elas têm profundas conexões com os rios que deságuam no mar.

São caminhos!

Rios, Montanhas e Crianças

Seres que nos ensinam.

Precisamos escutar mais

E respeitar a vida desses seres tão sagrados!

Foto: Maria Inês

Foto: Maria Inês

14/05/2024

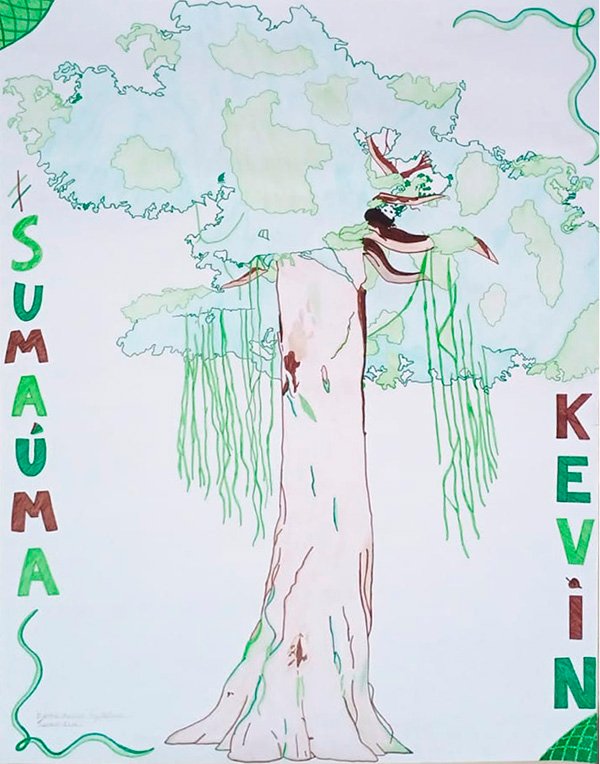

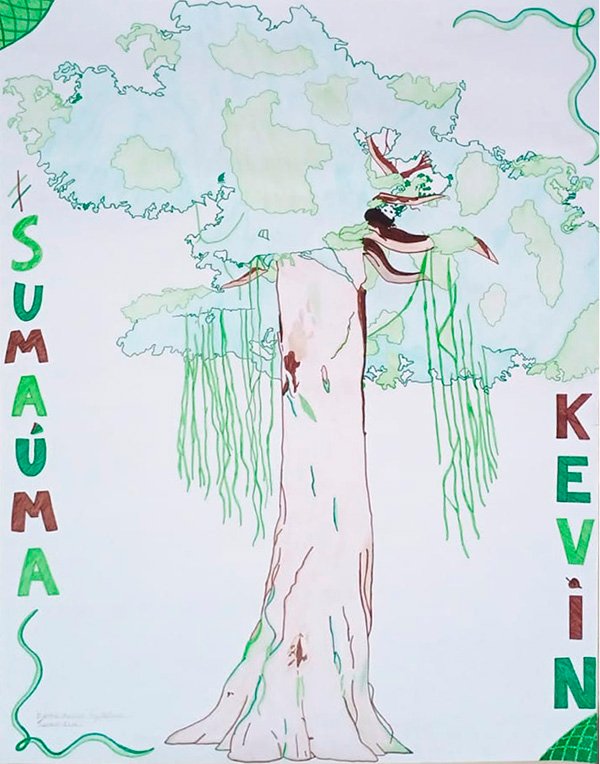

SUMAUMANOS – por Veronica Pinheiro

“Yuxin dacixunuan punyan daci we tsaua”,

“Todos os yuxin sentaram-se em todos os galhos da samaúma”.

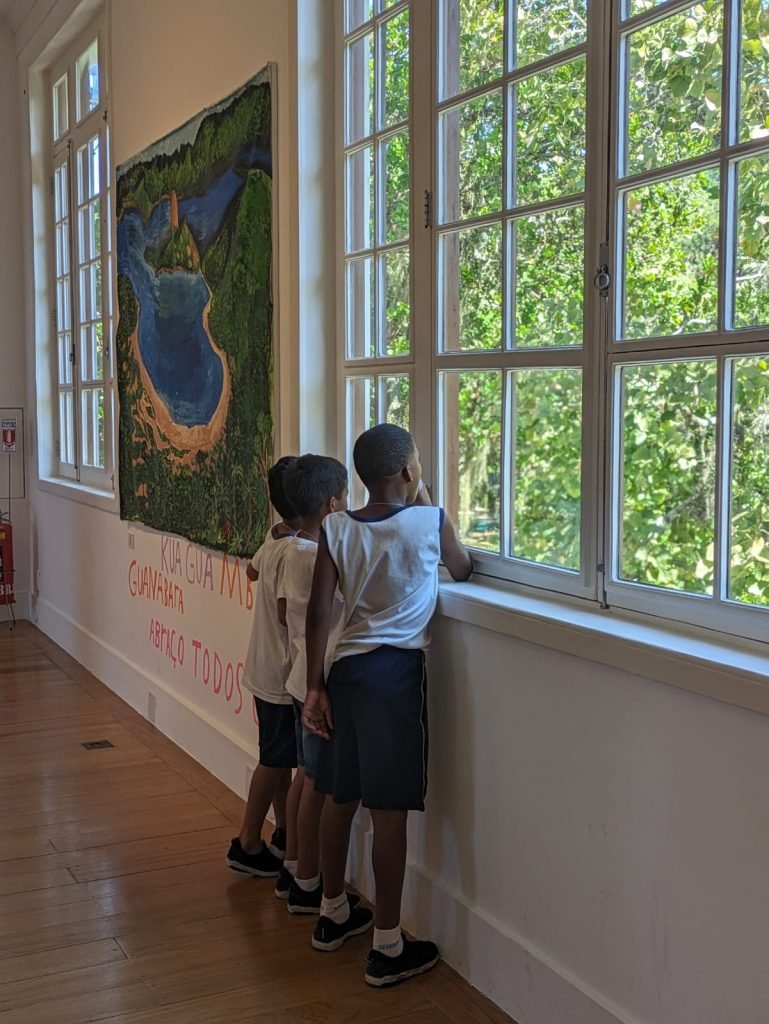

Às 7h30 do dia 07 de maio de 2024, a diretora, como todos os dias, abriu o portão da escola. No lugar de “bom dia”, ouvimos: “Não dormi de tanta alegria! Eu queria que amanhecesse logo pra vir pra escola.”

Pronunciadas as sentenças, ouvimos vozes sequenciadas como num jogral: “Eu também”. “Eu também”. “Eu também”.

Não reforcei o coro, mas eu também.

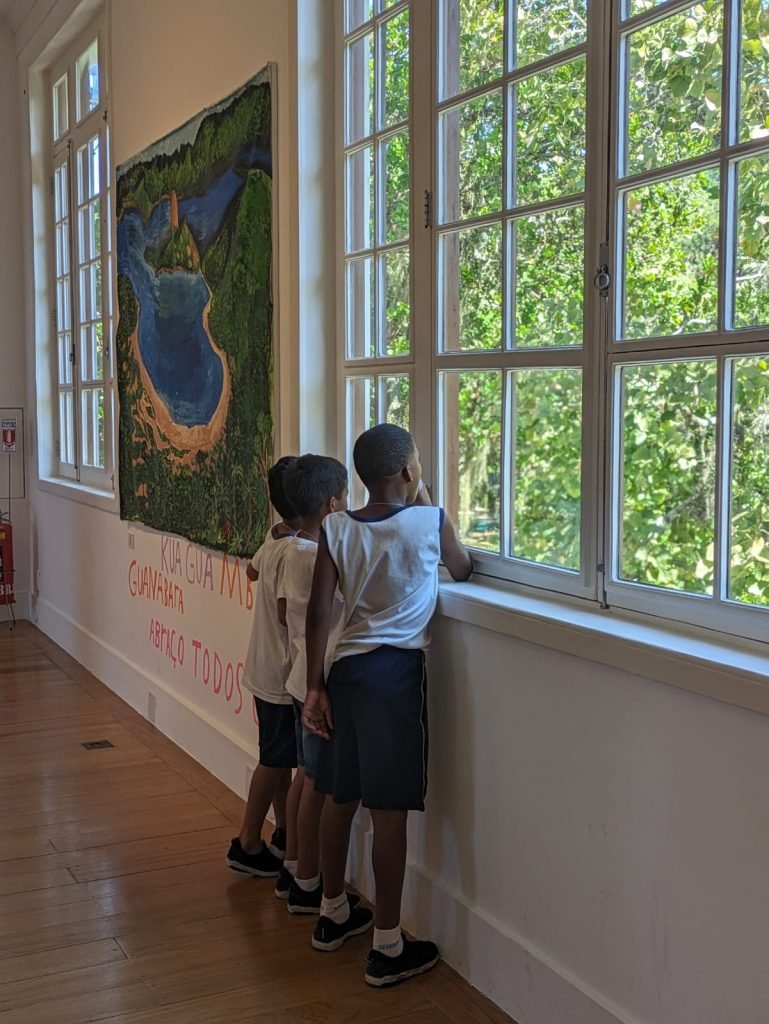

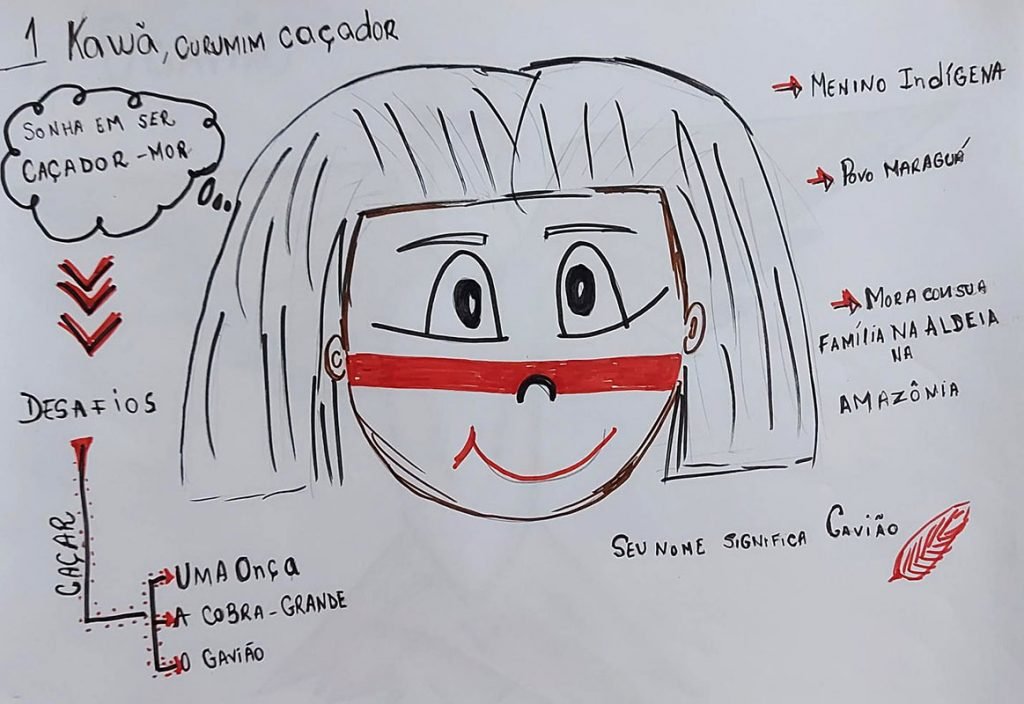

Era o dia da primeira imersão do Grupo Aprendizagens. Nosso destino: Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. Nesse movimento de despertamento de memórias, provocamos encontros. Alguns são entre espécies, outros não. Para nossa imersão pensamos no encontro das crianças com as árvores. Tínhamos um roteiro alinhavado: receber as crianças na escola; café da manhã; embarque no ônibus; chegada no Jardim Botânico; visita ao museu e à exposição Mbaé Kaá; passeio no jardim; piquenique; meditação e jogos teatrais; retorno à escola; e almoço. Uma linha longa e sensível prespontava de verde nossas expectativas.

Se “só existe o experimentar e o resto não nos diz respeito”¹, o que acontece quando, de forma sensível, aproximamos os seres urbanos que somos da natureza, que também somos? Muito provavelmente, chegaremos ao último diário do ano, em dezembro, sem a resposta, mas essa pergunta nos move. Repetidas vezes falamos em semeadura; em palavras germinantes. No cenário ideal, quem planta uma roça sabe o que vai colher e sabe o tempo de colheita do que foi plantado. E quem planta sonhos? Encontros? Quem planta água, árvores e florestas?

Levar as crianças ao Jardim Botânico para que elas encontrassem as árvores não compõe uma estratégia pedagógica. É muito mais simples: toda criança tem o direito de saber que é natureza e de ter acesso às manifestações do mundo natural.

“Tia, isso não é tiro. É fogos. Fica tranquila.” “Tia, esse barulho é do helicóptero da reportagem, o helicóptero da polícia tem outro barulho.” Na favela da Pedreira, muitas crianças de menos de 10 anos sabem reconhecer os sons do horror e da guerra. Porém, não conhecem os sons resultantes do encontro do vento com a copa das árvores. No dia 07 de maio de 2024, dia do passeio, a favela amanheceu tranquila e o Sol apareceu cedinho e bem quente, apesar de estarmos no outono. A última terça tinha gosto de docinho de festa.

Da escola, éramos um total de 42 pessoas². Do Grupo Aprendizagens, 6³. 1 ônibus rosa-choque e 1 motorista super gentil. A cor do ônibus é estratégica, precisamos entrar e sair da favela em segurança. O tal ônibus rosa se tornou uma personagem querida entre crianças e adultos, ele já ganhou nome e sua visita está sendo aguardada por outras turmas da escola.

A visita ao jardim começou e terminou diante da Sumaúma (Ceiba pentandra). No começo, “Sumaúma: Copa, Casa, Cosmos”, obra de Estevão Ciavatta com narração de Regina Casé, nos imergiu virtualmente na Sumaúma. Fomos recebidos pela equipe do educativo do Museu; Daiani Araújo e Thalyta Sousa receberam as crianças com muita delicadeza e conduziram todo o grupo até a obra Sumaúma. Na sala de projeção, todos, sem exceção, ouviram com o coração as palavras da árvore. Pela primeira vez, muitos dos presentes se deram conta que uma árvore tem muito a dizer sobre si e sobre a vida. Alguns quase não piscavam, outros ouviam de olhos fechados. Todos sorriam com lábios e olhos.

“Tia, faz o mapa pra chegar da escola até aqui. Quero trazer minha família pra ouvir a árvore.”

“Farei um mapa do metrô da Pavuna até aqui. Será muito fácil chegar.”

Subimos as escadas de madeira em pequenos grupos de 7 pessoas e no segundo andar, dentro da exposição Mbaé Kaá aprofundamos algumas conversas sobre plantas e a relação dos povos indígenas com elas, ao redor da instalação Jardim Viva Viva. Arte Guarani, natureza, ciência, Barbosa Rodrigues e as janelas do prédio. Após a conversa sobre a exposição, as crianças correram para janela. Ali me toquei que as janelas das salas de aula da escola não têm vista. O gesto coletivo de olhar para fora trouxe uma inquietação ao grupo. Muitos encontros estavam por acontecer. Abraços entre crianças e educadores do museu encerraram a primeira parte do passeio.

Dentro do Jardim, as crianças olhavam pra todas as direções possíveis. Enxergavam com olhos, ouvidos, pés, pele e coração. Pausa para admirar a água fresca descendo das pedras. Pausa para sentir o frescor das águas. Por um minuto ou mais não ouvi vozes; corações e bocas se calaram para o olho ver direito. Findo o silêncio que saudava as águas, aos poucos a euforia tomou novamente o grupo. “Não vou mais lavar essa mão aqui. Toquei na água da cachoeira.” Não falei nada. O menino acreditava que tinha tocado as águas, mal sabia que as águas tinham tocado nele. Ele agora carrega água fresca dentro, lavar ou não a mão é detalhe.

“Tia, o bambu falou!” Antes que eu tecesse algum comentário…

“Por que não tem panda lá em cima?”

Antes que eu falasse qualquer coisa… um peixe gigante, o tambaqui que vive no Lago Frei Leandro, se tornou mais interessante que a resposta. Caminhamos por alguns minutos, atravessamos a pequena ponte e o pequeno portal para o parquinho das crianças. Lá, tivemos uma pausa pro lanche e para meditação. Cantamos pra Terra. De olhos fechados fomos árvore. Raízes. Tronco. Galhos. Folhas. Nosso passeio se aproximava do fim, era hora de retornar ao ônibus. Pegamos um caminho diferente dentro do jardim, não poderíamos ir embora sem encontrar a Sumaúma plantada no Jardim.

Com raízes muito profundas que trazem água para a superfície mesmo na época seca, a Sumaúma é considerada a mãe da floresta and pode chegar a 70 metros, o que equivale a um edifício de 24 andares. De onde eu venho, na sumaúma vive Iroko, (do iorubá Íròkò) que é guardião da ancestralidade e dos antepassados, seio da natureza e morada de todos os Orixás; primeira árvore que se fez plantar na Terra. Muitos povos indígenas afirmam que as grandes sapopemas da sumaúma representam um portal para outro mundo. Uma árvore sagrada para diversos povos da floresta, uma grande mãe, que protege todos. Os Huni Kuï dizem “Yuxin dacixunuan punyan daci we tsaua”, “todos os yuxin sentaram-se em todos os galhos da samaúma”. Num espaço pluriversal de diálogos, a sumaúma é tudo isso e mais um pouco.

Li um documento da EMBRAPA sobre a Sumaúma e pensei que a equipe que escreveu o texto para o Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento deveria ter visitado o Jardim Botânico do Rio junto com as crianças, pois os técnicos do governo só conseguiram apresentar ao público os múltiplos usos e alternativas econômicas sobre a sumaúma. As crianças não. Assim como os babás e pajés, as crianças se conectaram com a árvore. Sonhos e seiva se misturaram. À medida que nossa roda se formava ao redor das sapopemas da sumaúma, memórias verdes eram despertadas. Em tempo de sonho, meus pequenos companheiros sonharam ser árvore e viver num jardim. Sonho é seiva, líquido que circula mantendo o tempo circular. Num tempo de seiva, Angélica de 10 anos chegou à seguinte conclusão: “Encontramos a árvore, entramos dentro dela agora somos SUMAUMANOS”.

Voltando à pergunta que nos movimenta: o que acontece quando, de forma sensível, aproximamos os seres urbanos que somos da natureza que também somos? Segundo a menina Angélica, podemos virar um pouco árvore.

¹in Mbaé Kaá o que tem na mata: A Botânica Nomenclatura Indígena, de João Barbosa Rodrigues. Dantes Editora, 2018.

² 37 alunos do 4º ano do Ensino Fundamental, 3 professores, coordenadora pedagógica e diretora adjunta

³ Luany da mediação de visita ao Jardim; Paula Novaes da mediação de atividade de respiração e jogos teatrais; Tania Grillo da mediação durante a exposição Mbaé Kaá, and 3 integrantes Group of the equipe de voluntários, Bia Jabor, Eliane Brígida, Evellyn.

Fotografia: Éricka Hoch;

Coordenação e medicação nas atividades de Veronica Pinheiro .

09/05/2024

TABACO, MESTRE DO SABER – por Cris Takuá

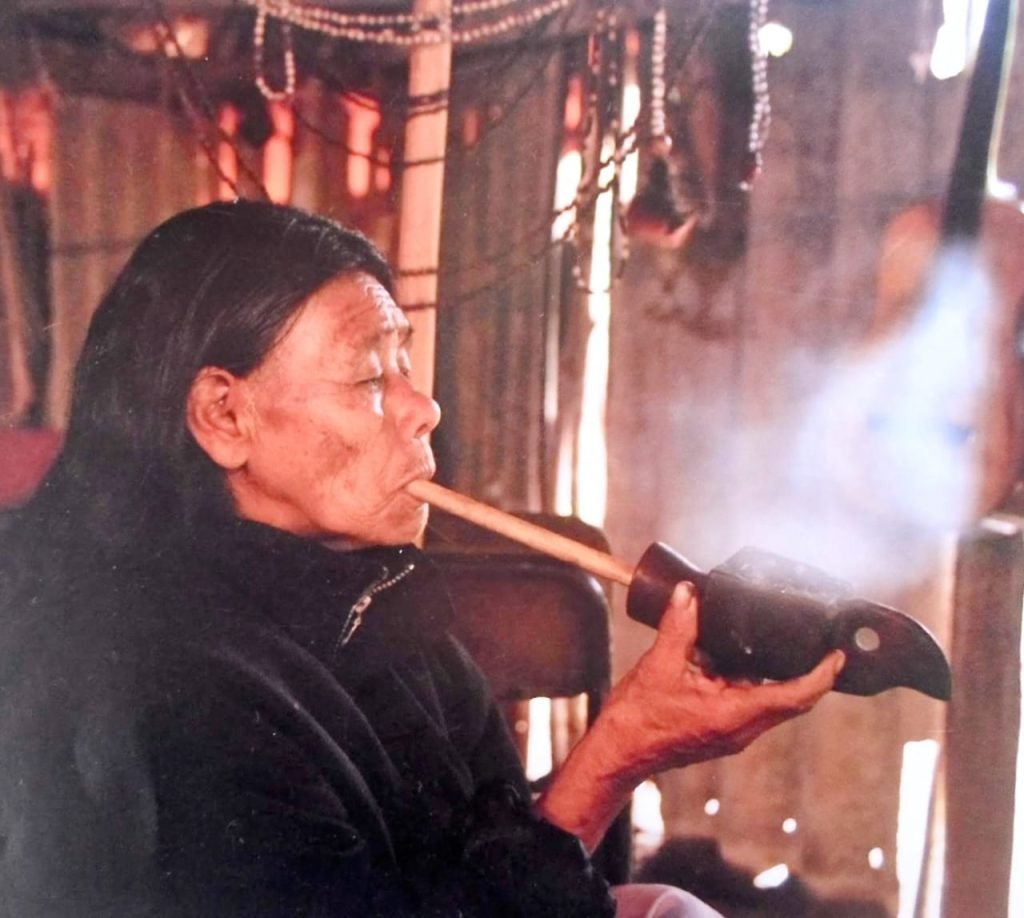

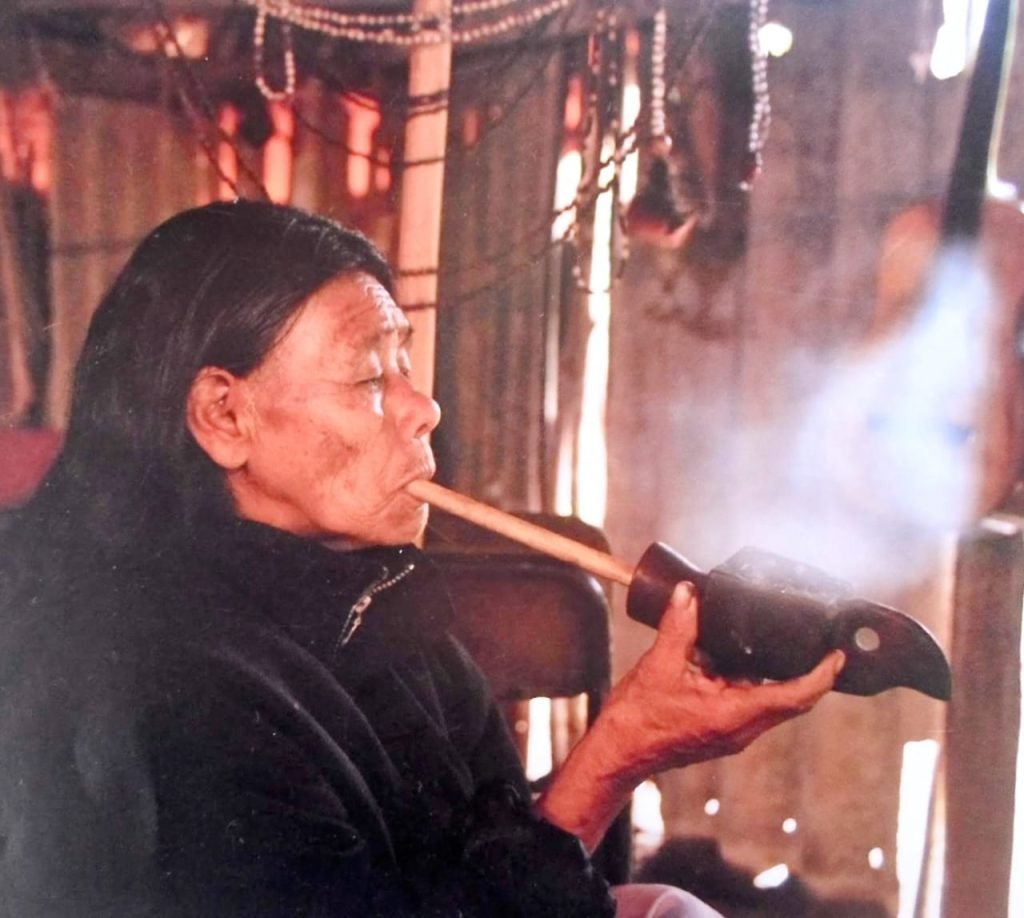

Foto: Carlos Papá

Foto: Carlos Papá

Curandeiro ancestral

O sopro do cachimbo

O sopro do rapé

O sopro do amor

Das palavras

Das canções que

Explodem do universo

Interior das inquietações íntimas

De nosso Ser…

O sopro limpa

Alivia e dissipa

As mágoas e as ansiedades.

A maldade existe!

Mas não é nada comparada

À força que habita na fumaça

Das medicinas sagradas

Que através de seu sopro

A tudo purifica e transforma

O sopro que como um impulso

Sai em forma de palavras em movimento

Ecoa pelos quatro cantos desse universo

Em profundos momentos .

É necessário cantar mais

Proferir mais palavras de amor

É necessário soprar cura a tudo e a todos

A ilusão persiste em perseguir

A matéria humana

Mas o verdadeiro Amor habita

Na sensível sabedoria

Das pequenas coisas

Dos pequenos atos

Das profundas ensenhanças

Dos sonhos e das crianças

Que revelam a cada novo amanhecer

A extraordinária beleza

De ser e existir plenamente.

O sopro me inundou a alma

Nessa noite silenciosa e fria

E através do sopro

Vi sua bela forma serena e tranquila

Me mostrando os caminhos

Me revelando os mistérios

Me apurando os sentidos

O sopro me aliviou

Me curou

E alegrou

E me fez poetizar ao amanhecer

As cantigas do bem viver!!!!!

(Sopro de palavras recebidas num amanhecer após um ritual de cura com tabaco)

Foto: Cris Takuá

Foto: Cris Takuá

Há milhares e milhares de tempos em meio ao escuro surgiu a vida e todos os seres que habitam ao nosso redor. Cada ser vegetal, animal, mineral são espíritos que convivem num profundo emaranhado de saberes, como uma grande teia onde tudo está conectado. Tudo que habita na Terra tem seu guardião e dono. Os Guarani chamam de Ija, os Maxakali de Yamiyxop, os Huni Kuin de Yuxibu, os Yanomami de Xapiri. Cada povo nomeia esse ser e mantem relação de profunda comunicação no mundo espiritual.

Não respeitar esses seres pode nos levar ao adoecimento. Por isso, as crianças precisam ser ensinadas desde pequenas a pedir licença por onde caminham, saber entrar e saber sair da floresta, da cachoeira, da montanha. Respeitar esses seres espíritos significa ter boa vida em equilíbrio e saúde.

Existem algumas plantas de poder, que também são chamadas de mestras, que nos mostram os caminhos, nos colocam em diálogo com os seres espíritos e também nos curam quando afetados por algum mal espiritual.

Muitas culturas indígenas em todas as partes do mundo historicamente fazem uso do tabaco para as suas práticas de cura. Essa planta sagrada está presente em culturas ancestrais em praticamente todos os continentes. Uns a utilizam em cachimbos que, através da fumaça baforada, proporcionam uma comunicação espiritual. Outros sopram o rapé. Ela pode também ser mascada ou tomada como água de tabaco para purga, proporcionando limpezas profundas. Também tem o uso externo como cataplasma. São muitos os usos desse ser.

Ailton Krenak, no Caderno Selvagem Entrar no mundo – Conversas sobre “Plantas Mestras”, em que dialoga com Carlos Papá, diz: “Aprendi então a fazer uma coisa que ainda não ouvi ninguém falando, que é de ler o tabaco. Sei que tem gente que lê borra de café, que lê outros movimentos na água. Mas só experimentei essa coisa de ler a mensagem do tabaco dichavado, sem nenhum uso, só ali olhando para ele me mostrando coisas. Foi muito bom. É provável que outras pessoas já tenham também vivido essa experiência em outros contextos, do tabaco ser essa voz de saúde, essa imagem ativa. Não é uma coisa inerte, mas é algo vivo. É claro que quem faz o uso ritual dele, o uso cotidiano dele, tem outras experiências.”

Percebemos, no entanto, que esse ser sagrado vem sendo tratado de forma desrespeitosa pelas sociedades humanas. As crianças crescem com medo do tabaco, pois são ensinadas que ele mata, causa câncer ou problemas pulmonares. Essa afirmação é carregada de um desconhecimento do uso dessa planta, pois, para muitas culturas que fazem uso ritualístico do tabaco, ele cura.

Tomio Kikuchi, em seu livro Essência do Oriente, diz: “Segundo o princípio Único da ordem do Universo Infinito, isto é, a dialética prática Ying-Yang, fumar tabaco é classificado na categoria Yang… Deve-se ter compreendido que fumar é yanguinizar-se. O câncer sendo Yinguinização explosiva, dilatação contínua (dominado que é pela força centrífuga Ying, dilatadora) será contrariado em seu desenvolvimento pela absorção da fumaça Yang constritora. Esta pode levar a sua regressão e finalmente à reabsorção… nós podemos declarar, com toda certeza, que fumar o tabaco é sobretudo recomendado para cancerosos como para todos aqueles que desejam que fortificar sua imunidade contra o câncer.”

Refletir sobre a profundeza dos seres plantas nessa relação íntima com nossas vidas significa mergulhar na ciência da floresta, que, ao longo de séculos, vem sendo ocultada e ignorada pela ciência capitalista e ocidental. Há um saber que rege comunicações muito sensíveis feitas através de tecnologias ancestrais, como a telepatia, a intuição e os sonhos. Os grandes rezadores e rezadoras, curandeiros e curandeiras passam tempos de suas vidas em processo de preparação para alcançar o entendimento para dialogar com as plantas professoras e possibilitar a cura aos humanos.

Ainda no diálogo Entrar no mundo, junto a Ailton Krenak, profundos pensamentos foram trazidos por Carlos Papá para que possamos sentir a delicada relação do tabaco para o povo Guarani.